Frontline Learning Research Vol.10 No. 2 (2022) 45 - 63

ISSN 2295-3159

aUniversity of Applied Sciences and Arts Northwestern Switzerland, School of Education, Switzerland

Article received 14 June 2022/ Revised 4 November 2022/ Accepted 10 November 2022/ Available online 22 December 2022

Motivation is a core element of teachers’ professional competences and, therefore, of great importance to teaching and learning. Motivation might explain why teachers do or do not promote self-regulated learning (SRL). Drawing on expectancy-value theory (EVT), this study used a person-centred approach to investigate to what extent multiple motivational aspects (self-efficacy; intrinsic interest, extrinsic utility, and attainment value; opportunity and effort costs) shape teachers’ motivational profiles. It examined the extent to which those profiles differ regarding experience in promoting SRL, the implicit theory of SRL, and the promotion of SRL. The study sample consisted of N = 280 in-service teachers (51.8% women; Mage = 44.34, SD = 10.82). Three profiles were identified: The high costs profile (profile 1, 30.8% of teachers), the moderate profile (profile 2, 24.4% of teachers), and the high success expectations and task values profile (profile 3, 44.8% of teachers). Further analyses revealed significant differences between these profiles concerning experience in promoting SRL, implicit theory of SRL, and the promotion of SRL, with Profile 1 showing the lowest values and Profile 3 the highest for each factor. The study found that high expectations are associated with high values, and costs are low when expectations and values are high and vice versa. This is in line with the assumptions of EVT and is applicable to all three profiles. These results indicate a clear need to support teachers in promoting SRL, especially those with high perceived costs, to ensure costs do not override the other considerations in EVT. Overall, this study is ‘frontline’ because it highlights the relevance of motivation as an aspect of teachers’ professional competences in promoting SRL. Furthermore, this study emphasizes the importance of combining EVT and SRL to provide a more nuanced picture of teachers’ motivation to promote SRL. It offers new insights that could influence the conceptualization of professional development programs for SRL.

Keywords: promotion of self-regulated learning; teacher motivation; expectancy-value theory; latent profile analysis; person-centred approach

Research has demonstrated that self-regulated learning (SRL) is essential to academic achievement and lifelong learning (Dent & Koenka, 2016). Self-regulated learning describes individuals as active and reflective learners who strategically monitor and regulate their learning to achieve goals. Self-regulated learning is a complex, dynamic, and effortful process that requires various cognitive, metacognitive, motivational, emotional, and behavioural competences (Pintrich, 2000). The high demands of SRL are reflected in the varying competence levels of learners (Dent & Koenka, 2016; Karlen, 2016). Thus, teachers must actively promote SRL in the classroom to empower students to become self-regulated learners (Thomas et al., 2020).

However, despite the emerging consensus that teachers can strengthen and support SRL (e.g., de Boer et al., 2018), SRL is rarely fostered in class (e.g., Dignath & Veenman, 2021). Why do teachers differ in their promotion of SRL? According to the integrative framework of Karlen et al. (2020), teachers’ professional competences in SRL – their knowledge of, belief in, and motivation to employ SRL – influences their classroom practices in promoting SRL. Various research studies have reported positive relationships between teachers’ professional competences in SRL and their promotion of SRL (De Smul et al., 2018; Karlen et al., 2020; Spruce & Bol, 2015; Thomas et al., 2020). Teachers’ motivation – especially self-efficacy – is a highly influential predictor of the promotion of SRL (Dignath, 2021). However, motivation is complex and cannot be explained by a single construct (Dörnyei & Ushioda, 2011) since motivational factors do not interact independently (Wigfield & Eccles, 2000). Therefore, additional motivational variables should be considered, as proposed by expectancy-value theory (EVT; Eccles & Wigfield, 2002). In the case of such complex interdependent constructs, and following the assertions of EVT, person-centred approaches such as latent profile analysis (LPA) are helpful because they allow researchers to view teachers as a system of interacting components (Magnusson, 1998; Nagin, 2005; Robins et al., 1998). Nevertheless, studies using person-centred approaches to examine teachers’ motivation for promoting SRL are rare (e.g., Dignath, 2021).

This study aims to address this shortcoming. It uses LPA, including various constructs of teachers’ motivation for the promotion of SRL derived from EVT, to address the question of the extent to which different motivational profiles emerge. Further, it analyses the extent to which the profiles differ regarding experience in promoting SRL, implicit theories of SRL, and the promotion of SRL. A deeper understanding of what motivates teachers to support SRL in their classrooms could contribute to the formulation of focused training efforts to ensure that teachers develop into professional and skilled promoters of SRL. This study is one of the first to combine EVT and SRL to provide an in-depth understanding of teachers’ motivational reasons for promoting or not promoting SRL.

For learners to become self-regulated learners, previous research has shown that they need explicit instruction from teachers regarding strategies in SRL and the opportunity to practice SRL in a powerful learning environment (e.g., De Corte et al., 2004; Dignath & Büttner, 2018; Dignath & Veenman, 2021). Therefore, to actively encourage SRL, teachers can engage in direct and indirect promotion of SRL. In direct promotion, teachers instruct students on SRL strategies and transmit strategy knowledge (e.g., explain why and how they can use specific SRL strategies). In indirect promotion, teachers provide a powerful learning environment that requires SRL and encourages students to be self-regulated learners; this environment allows students to engage with and practice the acquired strategies. Accordingly, teachers should combine direct and indirect promotion of SRL to empower students as much as possible (Paris & Paris, 2001).

However, various studies with a combined focus on direct and indirect strategy instruction at different school levels show that teachers tend to not extensively practice direct strategy instruction (Dignath & Büttner, 2018; Dignath van Ewijk et al., 2013; Kistner et al., 2010; Michalsky & Schechter, 2013; Spruce & Bol, 2015). Concerning indirect promotion, several studies have shown that prospective teachers use cooperative, situated, and problem-based learning only to some extent, even though it is considered beneficial for SRL (Dignath van Ewijk et al., 2013; Michalsky & Schechter, 2013).

Motivation is an essential prerequisite for effective instructional practice (Carson & Chase, 2009) and is considered a core element of teacher professionalism in SRL (Karlen et al., 2020). Expectancy-value theory has often been used to analyse teachers’ motivation for teaching but has not been applied to the context of their promotion of SRL. According to EVT, individuals are motivated when they expect a task to be successful and valuable (Eccles & Wigfield, 2002). Furthermore, researchers have recently been analysing costs as a third factor, whereas in earlier EVT, costs were a subcomponent of value (e.g., Barron & Hulleman, 2015). This section describes all three dimensions, their interplay, and the related research in the context of SRL.

Success expectations refer to a person’s perception of their competence to perform a future task (Wigfield & Eccles, 2000). Therefore, the expectancy component is based on the following assumption: If individuals believe they can do something, they are more likely to perform that behaviour (Eccles et al., 1998). Although a distinction was initially made between three types of expectancies (perception of ability, expectancies for success, and perceived performance), research has demonstrated that they are highly correlated and difficult to separate empirically (Eccles & Wigfield, 1995). Thus, the expectancy component forms a construct that can integrate different perspectives that focus on the belief that one can accomplish a task (Eccles & Wigfield, 2002), such as self-efficacy (Perez et al., 2018). In the context of SRL, self-efficacy and teaching practice are positively related (e. g., De Smul et al., 2019). When compared to teachers’ beliefs and knowledge, self-efficacy was the predictor with the largest direct effect on the self-reported promotion of SRL (e. g., Dignath-van Ewijk, 2016). Dignath (2021) performed one of the few person-centred studies that analysed competency profiles in promoting SRL, using self-efficacy as the motivational factor. In addition, she integrated teachers’ beliefs about and knowledge of SRL. The study identified two competence profiles regarding the promotion of SRL. The first profile showed low values overall, including in self-efficacy. In contrast, the second profile showed high values across the board. Both profiles displayed a positive relationship with the self-reported promotion of SRL.

Task values refer to a person’s valuation of a task and contribute to whether an individual will choose that task (Eccles, 2005). These valuations are subjective – individuals may evaluate the same task differently (Eccles & Wigfield, 2020). The value component is based on the following assumption: If individuals value something, they are more likely to perform that behaviour (Eccles et al., 1998). Four subjective task values are included in EVT (Eccles & Wigfield, 2002): intrinsic interest value, utility value, attainment value, and costs.

Eccles (2005) defines the intrinsic interest value as the pleasure or expected pleasure derived from performing the task. The utility value refers to the fit of the task with a person’s intentions. In other words, utility value reflects the task’s potential contribution to achieving a short- or long-term goal (Barron & Hulleman, 2015). Attainment value is the personal importance attached to engaging in a particular task. A task is considered important when a person sees engagement in the task as central to their sense of self and fulfilling a need that is important to them (Eccles, 2005).

These three values are positive reasons to engage in a task. Research indicates that teachers who rate the value of SRL as high are more likely to address and promote SRL in their classrooms (Vandevelde et al., 2012). Strong task values might encourage teachers to improve their knowledge and increase their efforts to promote SRL in class (Johnson & Sinatra, 2013; Peeters et al., 2016). Moreover, the value teachers place on SRL is positively related to their self-efficacy (success expectation) regarding the promotion of SRL, both of which can be claimed as predictors of SRL implementation in class (De Smul et al., 2019).

A fourth value factor, cost, can negatively influence the value of a task (Eccles (Parsons) et al., 1983). Cost was traditionally included under task value (Eccles & Wigfield, 2002; Wigfield & Eccles, 2000). However, increasing interest in and analysis of cost as a critical component of EVT (Barron & Hulleman, 2015) have resulted in cost being treated as a separate dimension (Flake et al., 2015; Jiang et al., 2018). Three types of costs have been identified: effort, opportunity, and emotional costs. Effort cost refers to an individual’s assessment of how much effort the task requires and whether it is worthwhile. Opportunity cost refers to the extent to which completing the task limits one’s ability or time for other essential tasks. Emotional cost refers to the expected anxiety associated with a task and the emotional and social costs of failure to complete the task (Eccles & Wigfield, 2002). Overall, individuals avoid tasks that cost too much relative to their utility, especially when compared to alternative tasks with a higher utility-cost ratio (Eccles (Parsons) et al., 1983). Research on teachers’ costs regarding the promotion of SRL is scarce. Vandevelde et al.’s (2012) research, which involved semi-structured interviews, reported that a lack of time, practical and material barriers, and work pressure were the greatest obstacles. Nevertheless, these results have not been supported by quantitative analysis.

In summary, the motivation to approach a task depends on various dimensions, such as the expectation of success, task values, and perceived costs. According to EVT (Eccles & Wigfield, 2002; Wigfield et al., 2009), an individual is motivated to perform a task if they feel competent to do so (high success expectation or self-efficacy scores), values the task (high intrinsic interest, extrinsic utility, and attainment value scores), and perceives the task has minimal costs (lower effort and opportunity cost scores). High expectations are associated with high values; furthermore, costs are low when expectations and values are high and vice versa. These findings are well documented in the case of students (e.g., Kosovich et al., 2017; Lazarides et al., 2019; Perez et al., 2018). However, research on teachers is still relatively scarce, especially concerning the promotion of SRL. The motivational aspect inherent to a teacher’s promotion of SRL has received little attention in the context of EVT. While empirical studies have examined this aspect, primarily by considering self-efficacy in variable-centred approaches (e.g., De Smul et al., 2018), person-centred approaches have rarely considered it (e.g., Dignath, 2021). In addition, few studies have focused on the value that teachers ascribe to SRL. Furthermore, research on costs has focused mainly on student SRL and rarely on teachers’ promotion of SRL.

In addition to examining the motivational aspects discussed above, research on the promotion of SRL has investigated teachers’ previous experiences and beliefs. Expectancy-value theory posits that teachers’ values and expectations of success, and consequently their choices and performance, depend on their experiences (Eccles et al., 1998). While positive experiences of success increase self-efficacy, negative experiences of failure can decrease it (Zimmerman & Ringle, 1981). Furthermore, while a positive experience increases perceived value, a negative experience decreases it (Wigfield & Eccles, 2000). For instance, Backfisch et al. (2020) found that teachers’ expertise (pre-service, trainee, and in-service teachers) related to their instructional quality and quality of technology exploitation, though this was mediated via teachers’ perceived-utility value. In the context of SRL specifically, teachers’ experience with autonomous learning, considered a form of indirect promotion of SRL, correlates with their self-reported promotion of SRL (Thomas et al., 2020). Lau (2013) further demonstrated that experienced teachers with instructional practices that comply with SRL-based instruction were better able to implement SRL-enhanced teaching. Hence, it is possible to assume that teachers with more experience in promoting SRL have higher motivation to do so and, in turn, show an increased promotion of SRL.

Regarding teachers’ belief systems, implicit theories are crucial because they act as individuals’ cognitive frameworks through which they interpret their experiences (Dweck & Leggett, 1988). Implicit theories are beliefs about abilities, which exist on a continuum from an entity theory (relatively fixed attributes) to an incremental theory (relatively malleable attributes). As such, implicit theories are critical predictors of an individual’s motivation (e.g., Burnette et al., 2013). Individuals with an incremental theory should be more motivated since the possibility of change increases success expectations, and, as EVT posits (Wigfield & Eccles, 2000), motivation depends on the expectation of success (Cook & Artino, 2016). As implicit theories of SRL are domain-specific, they relate to an individual’s beliefs specifically about the malleability of SRL (Hertel & Karlen, 2021). Individuals with an internalized entity theory of SRL assume that competences in SRL are relatively stable, so they cannot be enhanced by training. Individuals who espouse an incremental theory of SRL assume that SRL competences can change and be improved through training (Hertel & Karlen, 2021). Teachers who exhibit an incremental theory of SRL can therefore be expected to be more motivated to promote SRL than those with an entity theory and, consequently, show increased promotion of SRL.

Although EVT views motivation as multidimensional, many studies in the context of SRL have analysed the effects of single motivational characteristics, especially self-efficacy, employing variable-centred approaches. Little is known about several motivation aspects’ effects on teachers’ promotion of SRL. This study examines teachers’ motivation as a core element of their professional competences in promoting SRL. The research takes a person-centred approach, introducing EVT into the context of promoting SRL. Therefore, it has adapted and integrated self-efficacy and various value and cost factors. The study investigates the extent to which teachers display different motivational profiles regarding the promotion of SRL (Research Question 1). In addition, it examines the extent to which they differ in terms of experience in promoting SRL and implicit theories of SRL (Research Question 2). Furthermore, it analyses the extent to which these profiles differ concerning the promotion of SRL (Research Question 3).

Based on the theoretical explanations and empirical findings presented above, we hypothesise that teachers will display different motivational profiles regarding the promotion of SRL (Hypothesis 1). However, the lack of previous research on this topic means that this study uses an exploratory lens to elicit the number of profiles. Further, we hypothesise that teachers with different motivational profiles will have varying implicit theories of SRL. Teachers with more positive beliefs about the malleability of SRL will show a more motivated profile (higher self-efficacy, higher values, and lower cost scores; Hypothesis 2a). In addition, we hypothesise that teachers with different motivational profiles will have significantly different levels of experience in promoting SRL. Teachers with more experience promoting SRL will have a more motivated profile (Hypothesis 2b). Finally, we assume that teachers with different motivational profiles differ significantly regarding their promotion of SRL. Teachers with a more motivated profile will be likelier to report promoting SRL in class (Hypothesis 3).

Several lower-secondary schools (ISCED Level 2) were contacted via email, and their teachers were encouraged to participate in the study. N = 280 in-service teachers (51.8% women, 48.2% men) from 17 different schools finally participated, corresponding to a response rate of 92.1%. Participation was voluntary, and participants could withdraw at any time. Teachers were, on average, M = 44.34 years old (SD = 10.82, min = 23, max = 64) and had an average professional experience of M = 17.78 years (SD = 11.54).

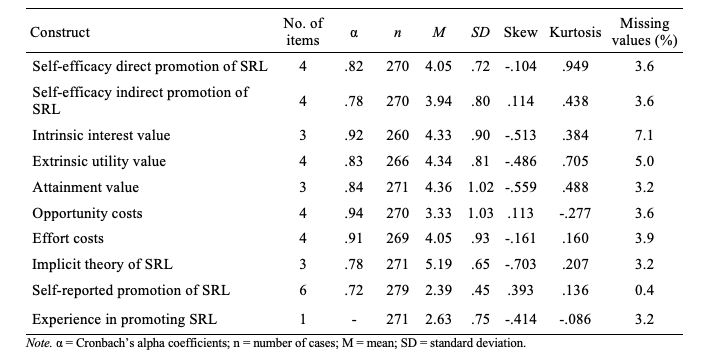

All instruments were assessed with an online questionnaire. The wording of the items for the profile analyses can be found in the Appendix, and those for the profile comparisons in section 2.2.2. All descriptive statistics and reliability values are shown in Table 1.

2.1.1 Measures for the Profile Analyses

Self-efficacy. Two validated scales from De Smul et al. (2018) were slightly shortened and used to assess expectancy concerning the promotion of SRL. We measured the self-efficacy regarding direct promotion of SRL (four items) and the self-efficacy regarding indirect promotion of SRL (four items). Each item was scored on a six-point scale from 1 (I cannot do that at all) to 6 (I can do that very well).

Values. Three scales were developed to measure the three subjective values concerning the promotion of SRL. We adapted Reinhard et al.’s (2015) scale to the context of the promotion of SRL to measure the intrinsic interest value (three items). To measure the extrinsic utility value, we used a self-developed scale based on the work of Eccles and Wigfield (2002; four items). We measured the attainment value using Gaspard et al.’s (2017) scale, adapting it to the context of promoting SRL and slightly shortening it (three items). Answers for all three value scales were provided on a six-point scale from 1 (does not apply at all) to 6 (entirely true).

Costs. To assess both the opportunity costs (four items) and effort costs (four items), we slightly shortened Flake et al.’s (2015) scales and adapted them to the context of the promotion of SRL. Answers for both cost scales were provided on a six-point scale from 1 (does not apply at all) to 6 (entirely true).

2.1.2 Measures for the Profile Comparisons

Experience in promoting SRL. Teachers’ previous experience in promoting SRL was measured using one item: «How much experience do you have in promoting self-organized learning in the classroom?». The item was scored on a four-point scale from 1 ((almost) no experience) to 4 (very much experience).

Implicit theory of SRL. We used a validated scale from Hertel and Karlen (2021) to assess the teachers’ implicit theories of SRL. The scale consists of three items (example item: «Everyone has a certain ability to self-regulate their learning, and this... (1) cannot be changed to (6) can be changed»).

Self-reported promotion of SRL. We developed a new self-report scale to measure the promotion of SRL. The six items include direct promotion (example item: «In my lessons, I explain to students why and how they can use a learning strategy for learning.») and indirect promotion of SRL (example item: «In my lessons, I create tasks that require students to use learning strategies they have learned.»). Answers were provided on a four-point scale from 1 ((almost) never) to 4 (in (almost) all lessons).

First, to verify that the constructs used for the latent profile analyses are consistent with the idea that the items measure seven separable dimensions, we conducted a confirmatory factor analysis (CFA, see section 3.1 and Appendix) in Mplus Version 8.1 (Muthén & Muthén, 1998-2017). We used robust maximum likelihood estimation (MLR) to account for non-normality (Li, 2016, see Table 2). We assessed model fit using different parameters: the comparative fit index (CFI), the Tucker-Lewis index (TLI), the root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA), and the standardized root mean square residual (SRMR). CFI and TLI values above 0.95 indicate an excellent model fit, and an RSMEA between 0.08 and 0.10 is acceptable (Hu & Bentler, 1999). These cut-off values also apply to the SRMR (Browne & Cudeck, 1992).

Second, we carried out LPA using Mplus Version 8.1 (Muthén & Muthén, 1998-2017) to identify the latent motivational profiles of teachers, which display as many similarities as possible within a profile and as many differences as possible between profiles (Lanza & Cooper, 2016). The full information maximum likelihood method accounted for missing values. Furthermore, we used the robust maximum likelihood estimator (MLR) to account for possible deviation from the multivariate normal distribution. LPA is a statistical procedure that merges individual cases into subgroups based on initial variables (Fong et al., 2021) – in our study, based on the EVT variables presented in section 2.2.1. Content considerations and different quality criteria were used to determine the number of profiles. Entropy (E) evaluates the quality of the measurement as a whole (Asparouhov & Muthén, 2014). The value should be greater than .80, which is true for average latent profile probabilities for the most likely latent profile membership. In addition, we used Bayesian information criterion (BIC) and Akaike information criterion (AIC) values, with lower values corresponding to a better-fitting model (Geiser, 2011). We also performed the Lo-Mendell-Rubin test (LMR) and bootstrap likelihood ratio test (BLR). For significant LMR and BLR tests, the data are better represented by the model with k profiles than k-1 profiles (Finch & Bronk, 2011). Additionally, the sample sizes of the profiles were considered.

Third, the profiles were tested using one-way analyses of variance (ANOVA) calculated with SPSS Statistics Version 27 to determine whether they differ in terms of experience in promoting SRL, implicit theory of SRL, and promotion of SRL in class (see section 2.2.2). Gabriel’s procedure was used for equal variances as post-hoc tests to identify specific group differences since the sample sizes vary slightly. When group variances were not identical, the Games-Howell procedure was used. Thus, the Type I error rate could be adequately controlled without a substantial loss in power (Field, 2009).

A CFA was conducted to verify that the constructs used for the LPAs measured seven separable dimensions. First, a one-dimensional model with a first-order factor and all 26 items was computed. The one-dimensional model yielded an unacceptable fit of X2 (299) = 2411.729, p < .001; RMSEA = 0.162 [90% CI = 0.156-0.168]; SRMR = 0.169; CFI = 0.481; TLI = 0.435, suggesting multidimensionality. Second, a three-dimensional model with three correlated latent factors (expectations, values, cost) was specified. This model showed better values on RMSEA and SRMR, but still not an acceptable fit for CFI and TLI, which should be above 0.95, according to Hu and Bentler (1999): X2 (296) = 955.368, p < .001; RMSEA = 0.091 [90% CI = 0.085–0.097]; SRMR = 0.087; CFI = 0.838; TLI = 0.822. Finally, a seven-dimensional model with seven correlated latent factors (two factors on expectations, three factors on values, two factors on costs) was calculated. The seven-factor CFA resulted in a good model fit: X2 (278) = 451.922, p < .001; RMSEA = 0.048 [90% CI = 0.040–0.056]; SRMR = 0.045; CFI = 0.957; TLI = 0.950. The standardized factor loadings of the seven factors with 26 items are listed in the Appendix. These results support the variables’ construct validity since, at a minimum, factorial validity exists; i.e., the items of the respective measurement instrument form a factor of their own (Bühner, 2011).

The average rate of cases with missing values per variable is 3.68% (range: 0.4% to 7.1%). Little’s MCAR test was performed to analyse the data for possible systematic missing values. The test proved to be nonsignificant (X2 = 99.845, df = 100, p = .486), meaning there are no systematic missing values in the data. All scales showed good to excellent reliability, with Cronbach’s α ranging from .72 to .94 (see Table 1). Table 2 shows the intercorrelations of the variables investigated.

Table 1

Descriptive Values and Internal Consistencies of the Measured Constructs

Table 2

Intercorrelations of the Measured Constructs

Table 3 shows the statistical fit indices for the three latent profile models computed. We concluded the three-profile model fit the data best since the four-profile solution reduced the BIC and AIC only slightly, increased entropy only slightly, resulted in a class size of 2%, and LMR was not found to be further statistically significant. Furthermore, as shown in the indices listed in Table 3, the three-profile solution also appears to fit the data better than the two-profile solution.

Table 3

Statistical Fit Indices for the Most Appropriate Profile Solutions

Therefore, LPA produced three significantly different motivational profiles of teachers (see Figure 1): The high costs profile (Profile 1), the moderate profile (Profile 2), and the high success expectations and task values profile (Profile 3). The first profile (30.8% of teachers) is characterized by relatively low scores on both expectancy components (self-efficacy regarding direct and indirect promotion of SRL), relatively low scores on the three value components (intrinsic interest, extrinsic utility, and attainment value), and relatively high scores on the cost components (opportunity and effort costs). The second profile includes 24.4% of the teachers examined and is characterized by relatively moderate scores (situated between Profiles 1 and 3) on all measured profile variables. The third and largest profile (44.8% of teachers) is characterized by relatively high scores on both expectancy components, relatively high scores on the three value components, and relatively low scores on the cost components.

The three profiles of teachers differ significantly regarding all latent profile indicators except for the component effort cost. Regarding effort costs, Profiles 1 and 2 and Profiles 1 and 3 differ significantly, but Profiles 2 and 3 do not (see Table 4).

Table 4

Descriptive Values by Profile and Differences Concerning Latent Profile Indicators

To analyse the extent to which the profiles differ according to various criteria, we used one-way ANOVA. The calculations show significant differences regarding experience in promoting SRL (Table 5). In this regard, Profiles 1 and 2 and Profiles 1 and 3 differ significantly, with Profile 1 having the least experience and Profile 3 having the most. There were also significant profile differences for implicit theories, with Profiles 1 and 3 and Profiles 2 and 3 differing significantly. Teachers in Profile 3 were most likely to state that SRL is malleable. Furthermore, the analyses revealed that the motivational profiles differed significantly in terms of the self-reported promotion of SRL, with Profiles 1 and 2 and Profiles 1 and 3 differing profoundly. Here, teachers in Profile 3 most often reported promoting SRL in their classrooms (Table 5).

Table 5

Descriptive Values by Profile and Differences Concerning Experience in Promoting SRL, Implicit Theory of SRL, and the Promotion of SRL

Research on teachers’ motivation to promote SRL has predominantly examined the relationship between teachers’ self-efficacy and their promotion of SRL. In line with EVT, additional motivational variables should be considered (Eccles & Wigfield, 2002). Therefore, this study aimed to provide a differentiated focus on motivation as an essential aspect of teachers’ professional competences in the promotion of SRL (Karlen et al., 2020). This study is one of the first to combine EVT and SRL. It applied EVT to the promotion of SRL and used LPAs integrating diverse expectancy, value, and cost components to examine various aspects of motivation in a differentiated manner.

The first research question aimed to determine the extent to which teachers display different motivational profiles regarding the promotion of SRL. To investigate this question, we examined several expectation, value, and cost components and computed LPAs in an exploratory manner. The results confirmed our first hypothesis: Three significantly different profiles emerged. The high costs profile (Profile 1; 30.8% of teachers) displayed comparatively low self-efficacy, low value, and high cost scores. The moderate profile (Profile 2; 24.4%) had relatively moderate scores on all variables, with expectations and values slightly higher than costs. The high success expectations and task values profile (Profile 3; 44.8%) showed comparatively high self-efficacy, high value, and low cost scores. These findings confirm that teachers have different success expectations, task values, and perceived costs regarding the promotion of SRL. For all three profiles, high expectations are associated with high values, and costs are low when expectations and values are high and vice versa. Thus, these EVT assumptions (Eccles & Wigfield, 2002; Wigfield et al., 2009), which so far have been documented especially for students (e.g., Kosovich et al., 2017; Lazarides et al., 2019; Perez et al., 2018), apply to all three motivational profiles of teachers identified in this investigation.

The second research question aimed to determine the extent to which teachers with different motivational profiles about the promotion of SRL differ in their implicit theory of SRL and their experience in promoting SRL. We assumed that teachers with more positive beliefs about the malleability of SRL would show a more motivated profile (higher self-efficacy, higher values, and lower cost scores; Hypothesis 2a). This hypothesis can be partially confirmed. Although the overall scores concerning the implicit theory of SRL for the three profiles are relatively high, the teachers in the high success expectations and task values profile (Profile 3) demonstrate the strongest belief that SRL is malleable. This finding is consistent with the EVT assumptions (Eccles & Wigfield, 2002). Individuals with an incremental theory are more motivated since the possibility of change increases expectations of success, and as the theory posits, motivation depends on these success expectations (Cook & Artino, 2016; Wigfield & Eccles, 2000). However, the differences between Profile 1 and 2 are insignificant. These findings may suggest that the degree of beliefs about the malleability of SRL must be very high to yield a difference in the promotion of SRL. Thus, a certain level of these beliefs would be required to promote SRL. Further investigations should clarify this threshold value.

Regarding experience in promoting SRL, the teachers in the different motivational profiles vary significantly. Teachers with greater experience in promoting SRL show a more highly motivated profile. However, the differences between Profiles 2 and 3 are not significant. Therefore, Hypothesis 2b can be partially confirmed. This finding is consistent with the theoretical assumptions of EVT (Eccles & Wigfield, 2002) and with previous empirical findings that experience can positively influence values (Backfisch et al., 2020; Lau, 2013; Thomas et al., 2020; Wigfield & Eccles, 2000) and success expectations (Eccles et al., 1998; Zimmerman & Ringle, 1981). High values and success expectations can cause teachers to engage in appropriate behaviour – in this case, the promotion of SRL. Again, the question arises: where exactly is the threshold level of experience such that it can exert a positive effect on motivational components? Further analyses are required to answer this.

The third research question aimed to determine the extent to which the self-reported promotion of SRL varies according to the teachers’ different motivational profiles. Our underlying assumption was that teachers with a more motivated profile (higher self-efficacy, higher values, and lower cost scores) are likelier to report that they promote SRL in class (Hypothesis 3). This hypothesis can be partially confirmed given that Profiles 1 and 2 and Profiles 1 and 3 differ significantly in this regard. Less motivated teachers (relatively low expectation and values scores and relatively high cost scores) differ from more motivated teachers (relatively high expectation and values scores and relatively low cost scores) in that they report promoting SRL less in class. Profiles 2 and 3, however, do not meaningfully differ. When comparing Profiles 2 and 3 with Profile 1, the success expectations and the values are more prominent than the costs in Profiles 2 and 3, while costs are higher than the success expectations and values in Profile 1. Thus, for the promotion of SRL, the ratio between the success expectations and values, on the one hand, and the costs, on the other hand, seems to be crucial (Eccles (Parsons) et al., 1983).

Remarkably, the effort costs are relatively high for all three motivational profiles. Therefore, even teachers in the high success expectations and task values profile (Profile 3) still face substantial obstacles in addressing the issue of SRL and its promotion in class. Previous research has shown that teachers still have relatively limited knowledge of SRL (CK-SRL) and its promotion (PCK-SRL; Barr & Askell-Williams, 2020; Karlen et al., 2020; Ohst et al., 2015) and that there are misconceptions (Glogger-Frey et al., 2018). Such limited knowledge or misconceptions could be a possible reason for the relatively high effort costs, as new knowledge must be acquired and misconceptions resolved. Other possible reasons could include a lack of time, practical and material barriers, and work pressure, as shown in Vandevelde et al.'s (2012) qualitative study. Whether these apply to this sample or whether there are other reasons for the increased effort costs would need to be investigated in further analyses. Nonetheless, teachers in motivational Profile 3 indicate that they promote SRL the most in their classes. Their strong task values might encourage these teachers to improve their knowledge and increase their effort to promote SRL in class (Johnson & Sinatra, 2013; Peeters et al., 2016).

Thus, the analyses revealed three profiles of teachers which all generally show a moderate level of motivation. Previous investigations have also identified such a moderate level of motivation (Karlen et al., 2020). Furthermore, teachers across the three motivational profiles scored moderately regarding the promotion of SRL in general. Other research has also shown that the promotion of SRL is relatively limited (Dignath & Büttner, 2018; Dignath & Veenman, 2021).

A few limitations should be considered when interpreting the results of this investigation. First, a person-centred approach has certain limitations, such as identifying qualitative profile differences (Morin & Marsh, 2015). To look at these profile differences in greater detail, we recommended that further research combines a variable and person-centred approach. Second, certain limitations, such as social desirability effects, can be expected with data based on self-report (Pekrun, 2020). While the anonymity of online questionnaires can limit these effects, they cannot be eliminated entirely (Sparfeldt et al., 2008).

Therefore, the results of this study, particularly concerning the promotion of SRL in the classroom, should be re-examined using other complementary methods, such as observation (Azevedo et al., 2018). Third, although two cost aspects (effort and opportunity costs) were included in the analyses, Eccles and Wigfield's (2002) model points to a third cost component that should be considered in further research to draw a holistic picture, namely emotional costs. Fourth, teachers’ emerging profiles were analysed for differences regarding a specific set of constructs. It would be of value to include further aspects, such as teachers’ knowledge regarding SRL (CK-SRL) and the promotion of SRL (PCK-SRL). Fifth, it would be interesting for future investigations to examine whether specific thresholds need to be met by teachers (e.g., experiences, implicit theories) to promote SRL in a way that is effective for learners. Finally, cross-sectional data shed light on momentary phenomena. A longitudinal design would help obtain information on the development of these motivational profiles of teachers regarding the promotion of SRL. Such findings could contribute considerably to clarifying the role of experience regarding the promotion of SRL in the motivation of teachers to promote and support SRL in class.

This study is one of the first to combine EVT and SRL and highlights the relevance of motivation as a subcomponent of teachers’ professional competences in promoting SRL (Karlen et al., 2020). The investigation demonstrated that it is crucial to integrate other motivational aspects besides self-efficacy to obtain a more nuanced picture of teachers’ motivation to promote SRL. The results of our study mainly align with EVT (Eccles & Wigfield, 2002) as they demonstrate that the interplay of different expectancy, value, and cost factors is related to teachers’ behaviour and, in this context, to the promotion of SRL. Specifically, teachers in the high-cost profile have the least experience in promoting SRL and report the lowest level of promoting SRL in class. Effort and opportunity costs seem tip the balance within the components of EVT such that costs override other considerations. Therefore, a clear need exists to support teachers in promoting SRL, especially those who perceive promoting SRL as having high costs. There are a few ways to reduce these costs: either by directly reducing the costs or by increasing the success expectations and task values. Teachers could be provided with materials for their lessons and practical promotion tips on combining curricular and cross-curricular content in everyday school life. Evidence exists that training and development content that is not costly to implement supports success expectations and effective implementation (e.g., Gaines et al., 2019). Success expectations can also be promoted through short-term training, which aims to develop teachers’ theoretical frameworks for SRL and SRL practice and empower them with practical competences on how to promote SRL. Such short-term training includes providing exercises that teachers can apply in their classes (e.g., Dignath, 2021). Concrete material such as exercises can also help teachers gain increased experience in promoting SRL, which reciprocally influences success expectations (Eccles et al., 1998; Zimmerman & Ringle, 1981) and can positively influence values (Backfisch et al., 2020; Lau, 2013; Thomas et al., 2020; Wigfield & Eccles, 2000). Such training aspects could be included in professional development programs to reduce, in particular, effort costs and increase success expectations and task values. Thus, the balance within the components of EVT could be such that the success expectations and task values override the costs, which in turn could be beneficial to the effective implementation of SRL promotion.

Additionally, teachers in the high cost profile and the moderate profile are less convinced of the malleability of SRL than those in the high success expectations and task values profile. Implicit theories seem to be influential for these two profiles in particular. Therefore, in addition to the practical implications already described, professional development programs should also address implicit theories of the malleability of SRL given that such theories are critical predictors of motivation and SRL behaviour (Burnette et al., 2013; Karlen et al., 2021) and, therefore, the promotion of SRL in class. In this context, Vosniadou et al. (2020) refer to conceptual change research, which finds that professional development programs can initiate possible changes in existing implicit theories by making participants aware of the theories and allowing them to discuss and reflect on them.

Overall, this study demonstrates that not only decreased costs and increased success expectations and task values are critical to the effective promotion of SRL by teachers in class but so is the belief that SRL is changeable and can be promoted. Therefore, professional development programs could benefit by explicitly addressing the reduction of costs, increasing expectations and values, and bringing awareness to implicit theories. This approach could prevent costs from overriding other factors in the EVT.

The research reported in this publication was supported by the Swiss National Science Foundation – project number 100019-189133 / 1.

Asparouhov, T., & Muthén, B. O. (2014). Variable-specific entropy contribution. Mplus. https://www.statmodel.com/download/UnivariateEntropy.pdf

Azevedo, R., Taub, M., & Mudrick, N. V. (2018). Using multi-channel trace data to infer and foster self-regulated learning between humans and advanced learning technologies. In D. Schunk & J. A. Greene (Eds.), Handbook of self-regulation of learning and performance (Vol. 2, pp. 254–270). Routledge.

Backfisch, I., Lachner, A., Hische, C., Loose, F., & Scheiter, K. (2020). Professional knowledge or motivation? Investigating the role of teachers’ expertise on the quality of technology-enhanced lesson plans. Learning and Instruction, 66, 101300. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.learninstruc.2019.101300

Barr, S., & Askell-Williams, H. (2020). Changes in teachers’ epistemic cognition about self-regulated learning as they engaged in a researcher-facilitated professional learning community. Asia-Pacific Journal of Teacher Education, 48(2), 187–212. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/1359866X.2019.1599098

Barron, K. E., & Hulleman, C. S. (2015). Expectancy-value-cost model of motivation. In J. D. Wright (Ed.), International encyclopedia of the social & behavioral sciences (Second edition) (Vol. 8, pp. 503–509). Elsevier. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-08-097086-8.26099-6

Browne, M. W., & Cudeck, R. (1992). Alternative ways of assessing model fit. Sociological Methods & Research, 21(2), 230–258. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/0049124192021002005

Bühner, M. (2011). Einführung in die Test- und Fragebogenkonstruktion [Introduction to test and questionnaire construction] . Pearson Studium.

Burnette, J. L., O’Boyle, E., VanEpps, E. M., Pollack, J. M., & Finkel, E. J. (2013). Mindsets matter: A meta-analytic review of implicit theories and self-regulation. Psychological Bulletin, 139(3), 655–701. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1037/a0029531

Carson, R. L., & Chase, M. A. (2009). An examination of physical education teacher motivation from a self-determination theoretical framework. Physical Education and Sport Pedagogy, 14(4), 335–353. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/17408980802301866

Cook, D. A., & Artino, A. R. (2016). Motivation to learn: an overview of contemporary theories. Medical Education, 50(10), 997–1014. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/medu.13074

de Boer, H., Donker, A. S., Kostons, D. D. N. M., & van der Werf, G. P. C. (2018). Long-term effects of metacognitive strategy instruction on student academic performance: A meta-analysis. Educational Research Review, 24, 98–115. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.edurev.2018.03.002

De Corte, E., Verschaffel, L., & Masui, C. (2004). The CLIA-model: A framework for designing powerful learning environments for thinking and problem solving. European Journal of Psychology of Education, 19(4), 365–384. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF03173216

De Smul, M., Heirweg, S., Devos, G., & Van Keer, H. (2019). School and teacher determinants underlying teachers’ implementation of self-regulated learning in primary education. Research Papers in Education, 34(6), 701–724. https://doi.org/10.1080/02671522.2018.1536888

De Smul, M., Heirweg, S., Van Keer, H., Devos, G., & Vandevelde, S. (2018). How competent do teachers feel instructing self-regulated learning strategies? Development and validation of the teacher self-efficacy scale to implement self-regulated learning. Teaching and Teacher Education, 71, 214–225. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2018.01.001

Dent, A. L., & Koenka, A. C. (2016). The relation between self-regulated learning and academic achievement across childhood and adolescence: A meta-analysis. Educational Psychology Review, 28(3), 425–474. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10648-015-9320-8

Dignath-van Ewijk, C. (2016). Which components of teacher competence determine whether teachers enhance self-regulated learning? Predicting teachers’ self-reported promotion of self-regulated learning by means of teacher beliefs, knowledge, and self-efficacy. Frontline Learning Research, 4(5), 83–105. https://doi.org/http://dx.doi.org/10.14786/flr.v4i5.247

Dignath, C. (2021). For unto every one that hath shall be given: teachers’ competence profiles regarding the promotion of self-regulated learning moderate the effectiveness of short-term teacher training. Metacognition and Learning, 16(3), 555–594. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s11409-021-09271-x

Dignath, C., & Büttner, G. (2018). Teachers’ direct and indirect promotion of self-regulated learning in primary and secondary school mathematics classes – insights from video-based classroom observations and teacher interviews. Metacognition Learning, 13(2), 127–157. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s11409-018-9181-x

Dignath, C., & Veenman, M. V. J. (2021). The role of direct strategy instruction and indirect activation of self-regulated learning—Evidence from classroom observation studies. Educational Psychology Review, 33(2), 489–533. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s10648-020-09534-0

Dignath van Ewijk, C., Dickhäuser, O., & Büttner, G. (2013). Assessing how teachers enhance self-regulated learning: A multiperspective approach. Journal of Cognitive Education and Psychology, 12(3), 338–358. https://doi.org/http://dx.doi.org/10.1891/1945-8959.12.3.338

Dörnyei, Z., & Ushioda, E. (2011). Teaching and researching motivation. Pearson.

Dweck, C. S., & Leggett, E. L. (1988). A social-cognitive approach to motivation and personality. Psychological Review, 95(2), 256–273. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-295X.95.2.256

Eccles (Parsons), J. S., Adler, T. F., Futterman, R., Goff, S. B., Kaczala, C. M., Meece, J. L., & Midgley, C. (1983). Expectancies, values, and academic behaviors. In J. T. Spence (Ed.), Achievement and Achievement Motivation (pp. 75–146). W. H. Freeman.

Eccles, J. S. (2005). Subjective task value and the Eccles et al. model of achievement-related choices. In A. J. Elliot & C. S. Dweck (Eds.), Handbook of competence and motivation (pp. 105–121). Guilford.

Eccles, J. S., & Wigfield, A. (1995). In the mind of the actor: The structure of adolescents' achievement task values and expectancy-related beliefs. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 21 (3), 215–225. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167295213003

Eccles, J. S., & Wigfield, A. (2002). Motivational beliefs, values, and goals. Annual Review of Psychology, 53(1), 109–132. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.psych.53.100901.135153

Eccles, J. S., & Wigfield, A. (2020). From expectancy-value theory to situated expectancy-value theory: A developmental, social cognitive, and sociocultural perspective on motivation. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 61, 101859. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cedpsych.2020.101859

Eccles, J. S., Wigfield, A., & Schiefele, U. (1998). Motivation. In N. Eisenberg (Ed.), Handbook of child psychology (Vol. 3, pp. 1017–1095). Wiley.

Field, A. (2009). Discovering statistics using SPSS (and sex and drugs and rock 'n' roll) . SAGE.

Finch, H. W., & Bronk, K. C. (2011). Conducting confirmatory latent class analysis using Mplus.Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal, 18(1), 132–151. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/10705511.2011.532732

Flake, J. K., Barron, K. E., Hulleman, C. S., McCoach, B. D., & Welsh, M. E. (2015). Measuring cost: The forgotten component of expectancy-value theory. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 41, 232–244. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cedpsych.2015.03.002

Fong, C. J., Kremer, K. P., Hill-Troglin Cox, C., & Lawson, C. A. (2021). Expectancy-value profiles in math and science: A person-centered approach to cross-domain motivation with academic and STEM-related outcomes. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 65, 101962. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cedpsych.2021.101962

Gaines, R. E., Osman, D. J., Maddocks, D. L. S., Warner, J. R., Freeman, J. L., & Schallert, D. L. (2019). Teachers’ emotional experiences in professional development: Where they come from and what they can mean. Teaching and Teacher Education, 77, 53–65. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2018.09.008

Gaspard, H., Häfner, I., Parrisius, C., Trautwein, U., & Nagengast, B. (2017). Assessing task values in five subjects during secondary school: Measurement structure and mean level differences across grade level, gender, and academic subjec. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 48, 67–84. https://doi.org/http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.cedpsych.2016.09.003

Geiser, C. (2011). Datenanalyse mit Mplus. Eine anwendungsorientierte Einführung [Data analysis with Mplus. An application-oriented introduction] . VS Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften.

Glogger-Frey, I., Ampatziadis, Y., Ohst, A., & Renkl, A. (2018). Future teachers’ knowledge about learning strategies: Misconcepts and knowledge-in-pieces. Thinking Skills and Creativity, 28, 41–55. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tsc.2018.02.001

Hertel, S., & Karlen, Y. (2021). Implicit theories of self-regulated learning: Interplay with students’ achievement goals, learning strategies, and metacognition. British Journal of Educational Psychology, 91(3), e12402. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjep.12402

Hu, L. t., & Bentler, P. M. (1999). Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives.Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal, 6(1), 1–55. https://doi.org/10.1080/10705519909540118

Jiang, Y., Rosenzweig, E. Q., & Gaspard, H. (2018). An expectancy-value-cost approach in predicting adolescent students’ academic motivation and achievement. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 54, 139–152. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cedpsych.2018.06.005

Johnson, M. L., & Sinatra, G. M. (2013). Use of task-value instructional inductions for facilitating engagement and conceptual change. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 38(1), 51–63. https://doi.org/http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.cedpsych.2012.09.003

Karlen, Y. (2016). Differences in students' metacognitive strategy knowledge, motivation, and strategy use: A typology of self-regulated learners. The Journal of Educational Research, 109(3), 253–265. https://doi.org/http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/00220671.2014.942895

Karlen, Y., Hertel, S., & Hirt, C. N. (2020). Teachers’ professional competences in self-regulated learning: An approach to integrate teachers’ competences as self-regulated learners and as agents of self-regulated learning in a holistic manner [Original Research]. Frontiers in Education, 5, 159. https://doi.org/10.3389/feduc.2020.00159

Karlen, Y., Hirt, C. N., Liska, A., & Stebner, F. (2021). Mindsets and Self-Concepts about self-regulated learning: Their relationships with emotions, strategy knowledge, and academic achievement. Frontiers in Psychology, 12, 661142. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.661142

Kistner, S., Rakoczy, K., Otto, B., Dignath-van Ewijk, C., Büttner, G., & Klieme, E. (2010). Promotion of self-regulated learning in classrooms: Investigating frequency, quality, and consequences for student performance. Metacognition and Learning, 5(2), 157–171. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11409-010-9055-3

Kosovich, J. J., Flake, J. K., & Hulleman, C. S. (2017). Short-term motivation trajectories: A parallel process model of expectancy-value. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 49, 130–139. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cedpsych.2017.01.004

Lanza, S. T., & Cooper, B. R. (2016). Latent class analysis for developmental research. Child Development Perspectives, 10(1), 59–64. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/cdep.12163

Lau, K. L. (2013). Chinese language teachers' perception and implementation of self-regulated learning-based instruction. Teaching and Teacher Education, 31, 56–66. https://doi.org/http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2012.12.001

Lazarides, R., Dietrich, J., & Taskinen, P. H. (2019). Stability and change in students’ motivational profiles in mathematics: The role of perceived teaching. Teaching and Teacher Education, 79, 164–175. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2018.12.016

Li, C.-H. (2016). Confirmatory factor analysis with ordinal data: Comparing robust maximum likelihood and diagonally weighted least squares. Behavior Research Methods, 48(3), 936–949. https://doi.org/10.3758/s13428-015-0619-7

Magnusson, D. (1998). The logic and implications of a person-oriented approach. In R. B. Cairns, L. R. Bergman, & J. Kagan (Eds.), Methods and models for studying the individual: Essays in honor of Marian Radke-Yarrow (pp. 33–64). Sage.

Michalsky, T., & Schechter, C. (2013). Preservice teachers’ capacity to teach self-regulated learning: Integrating learning from problems and learning from successes. Teaching and Teacher Education, 30, 60–73. https://doi.org/http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2012.10.009

Morin, A. J. S., & Marsh, H. W. (2015). Disentangling shape from level effects in personcentered analyses: An illustration based on university teachers’ multidimensional profiles of effectiveness.Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal, 22(1), 39–59. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/10705511.2014.919825

Muthén, L. K., & Muthén, B. O. (1998-2017). Mplus User's Guide. Eighth Edition. Muthén & Muthén. https://www.statmodel.com/download/usersguide/MplusUserGuideVer_8.pdf

Nagin, D. S. (2005). Group-based modeling of development. Harvard Press.

Ohst, A., Glogger, I., Nückles, M., & Renkl, A. (2015). Helping preservice teachers with inaccurate and fragmentary prior knowledge to acquire conceptual understanding of psychological principles. Psychology Learning & Teaching, 14(1), 5–25. https://doi.org/10.1177/1475725714564925

Paris, S. G., & Paris, A. H. (2001). Classroom applications of research on selfregulated learning. Educational Psychologist, 36 (2), 89–101. https://doi.org/10.1207/S15326985EP3602_4

Peeters, J., De Backer, F., Kindekens, A., Triquet, K., & Lombaerts, K. (2016). Teacher differences in promoting students' self-regulated learning: Exploring the role of student characteristics. Learning and individual Differences, 52, 88–96. https://doi.org/http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.lindif.2016.10.014

Pekrun, R. (2020). Commentary: Self-report is indispensable to assess students’ learning. Frontline Learning Research, 8(3), 185–193. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.14786/flr.v8i3.637

Perez, T., Wormington, S. V., Barger, M. M., Schwartz-Bloom, R. D., Lee, Y.-k., & Linnenbrink-Garcia, L. (2018). Science expectancy, value, and cost profiles and their proximal and distal relations to undergraduate science, technology, engineering, and math persistence. Science Education, 103(2), 264–286. https://doi.org/10.1002/sce.21490

Pintrich, P. R. (2000). The role of goal orientation in self-regulated learning. In M. Boekaerts, P. R. Pintrich, & M. Zeidner (Eds.), Handbook of self-regulated learning (pp. 451–502). Academic Press. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-012109890-2/50043-3

Reinhard, M.-A., Schindler, S., & Dickhäuser, O. (2015). Effects of subjective task values and information processing on motivation formation. International Journal of Psychological Studies, 7(3), 58–66. https://doi.org/http://dx.doi.org/10.5539/ijps.v7n3p58

Robins, R. W., John, O. P., & Caspi, A. (1998). The typological approach to studying personality. In R. B. Cairns, L. R. Bergman, & J. Kagan (Eds.), Methods and models for studying the individual: Essays in honor of Marian Radke-Yarrow (pp. 135–160). Sage.

Sparfeldt, J. R., Burch, S. R., Rost, D. H., & Lehmann, G. (2008). Akkuratesse selbstberichteter Zensuren [Accuracy of self-reported grades]. Psychologie in Erziehung und Unterricht, 55, 68–75. https://www.reinhardt-journals.de/index.php/peu/article/download/501/2500

Spruce, R., & Bol, L. (2015). Teacher beliefs, knowledge, and practice of self-regulated learning. Metacognition and Learning, 10(2), 245–277. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11409-014-9124-0

Thomas, V., Peeters, J., DeBacker, F., & Lombaerts, K. (2020). Determinants of self-regulated learning practices in elementary education: A multilevel approach. Educational Studies, 48(1), 126–148. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/03055698.2020.1745624

Vandevelde, S., Vandebussche, L., & Van Keer, H. (2012). Stimulating selfregulated learning in primary education: Encouraging versus hampering factors for teachers. Procedia - Social and Behavioral Sciences, 69, 1562–1571. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2012.12.099

Vosniadou, S., Lawson, M. J., Wyra, M., Van Deur, P., Jeffries, D., & Darmawan, I. (2020). Pre-service teachers’ beliefs about learning and teaching and about the self-regulation of learning: A conceptual change perspective. International Journal of Educational Research, 99, 101495. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijer.2019.101495

Wigfield, A., & Eccles, J. S. (2000). Expectancy–value theory of achievement motivation. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 25(1), 68–81. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1006/ceps.1999.1015

Wigfield, A., Tonks, S., & Klauda, S. L. (2009). Expectancy‐value theory. In K. R. Wentzel & A. Wigfield (Eds.), Handbook of motivation at school (pp. 55–75). Routledge.

Zimmerman, B. J., & Ringle, J. (1981). Effects of model persistence and statements of confidence on children's self-efficacy and problem solving. Journal of Educational Psychology, 73 (4), 485–493. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0663.73.4.485