Frontline Learning Research Special Issue Vol.8

No.5 (2020) 5 - 23

ISSN 2295-3159

aUniversity of Education Upper

Austria, Austrian

bUniversity of Duisburg-Essen, Germany

cUniversity of Leipzig, Germany

dGoethe University Frankfurt am Main, Germany

eCity of Hannover, Bereich Migration und Integration,

Hannover, Germany

Article received 11 June 2018 / revised 7 October/ accepted 12 December 2019 / available online 1 July 2020

Research on the Happy Victimizer Phenomenon has mainly focused on preschool and schoolchildren, with a few studies also including adolescents and young adults. The main finding is that young children, despite knowing that harming somone is wrong, ascribe positive feelings to perpetrators and offer hednonistic justifications, interpreted as a lack of moral motivation. Only at age 9 or 10 do almost all children ascribe negative feelings to perpetrators. According to the developmental transition hypothesis, the phenomenon should disappear in late childhood. However, reasoning patterns resembling that of the Happy Victimizer have been found in studies with adolescents and young adults, challenging that hypothesis. We present findings from four studies involving adolescents and young adults to give an overview of the patterns found and the measurement approaches used. Finally, we critically discuss the limitations of those studies and raise some core theoretical and methodological issues that remain to be resolved, some of them being addressed in the remaining papers of this special issue. The four studies and the paper are innovative in that (a) situational factors are included in the measurement of the moral reasoning patterns; (b) new reasoning patterns are identified in the context of an extended measurement approach; and (c) the moral reasoning patterns are investigated in their own right and not used as potential explanatory variables for behaviour, as has been the main focus of research on the Happy Victimizer Phenomenon so far.

Keywords: Happy Victimizer Pattern, adolescence, adulthood, situation specifity

The present paper focuses on the development of morality in the context of evaluating moral rule transgressions. Our conceptualisation of morality refers to the prescriptive (or normative) aspect of morality (as distinct from the descriptive aspect) and relates to a code of behaviour which – if specific requirements are met – might be endorsed by all rational individuals (Gert, 2012). Moreover, the moral domain can be distinguished from the domain of social conventions and personal issues (Smetana, 2006). Moral issues refer to behavioural choices affecting the rights and welfare of others, that is, the “right and good”, requiring humans to show benevolence and kindness towards others (Gibbs, 2003), with the aim of not harming, protecting, or restoring others’ welfare (Gutzwiller-Helfenfinger, 2015). To realise this, we need to overcome our own, egocentric, self-interested viewpoint and take a more “objective”, moral point of view lying outside ourselves (Baier, 1965). Often, people experience moral conflicts in situations where following their own needs and desires would entail violating the rights and welfare of others. Transgressing a moral rule therefore means that others’ rights or welfare are harmed, for example by hitting or stealing from another person. Research within the Happy Victimizer Phenomenon more closely investigates the way children, adolescents, and adults make sense of situations where a protagonist breaks a moral rule.

The first empirical study investigating the Happy Victimizer Phenomenon as such was presented by Nunner-Winkler and Sodian (1988), although a few earlier studies had already addressed children’s emotion expectancies regarding a variety of social events (e.g., Barden, Zelko, Duncan, & Master, 1980). Nunner-Winkler and Sodian (1988) found that four-year-old children stated that an individual has positive emotions after a rule transgression, even though they knew that the rule transgression was wrong. By contrast, eight-year-old children, after having judged the transgression as wrong, attributed negative emotions to the transgressor. According to functionalist theories of emotions, emotions are understood as internal control and evaluation systems motivating human behaviour (Bretherton, Fritz, Zahn-Waxler, & Ridgeway, 1986, p. 530). Therefore, Nunner-Winkler and Sodian (1988) interpreted the pattern of judging the transgression as wrong while attributing positive emotions to the transgressor as an indicator of lower moral motivation in early compared to later childhood. While this pattern has been confirmed in numerous studies, research involving late childhood and adolescence is rare and has yielded incongruent results regarding the development of moral motivation. For instance, while Nunner-Winkler (2008) showed an increase of moral motivation between the ages of four and 23 years, Krettenauer (2011) as well as Malti and Buchmann (2010) found no age differences in the strength of moral motivation during adolescence.

However, none of the studies presented focused on the development of moral motivation from late childhood to adolescence and adulthood. Yet there seems to be evidence that at least some adults show psychological patterns similar to the Happy Victimizer Phenomenon (HVP) (Nunner-Winkler, 2007), that is, deciding in favor of a moral transgression (“defection”) in order to fulfil one’s own needs while experiencing positive emotions (and no remorse). Additionally, findings from other disciplines report patterns of moral decision-making quite similar to the basic structure of the HVP. This includes research from behavioural economics (e.g., Andreoni & Bernheim, 2009; Dana, Weber & Kuang, 2007; List, 2007), research on moral harzard and free riding in teams (Anesi, 2009) or research on academic cheating (Klein Schiphorst, 2013). Thus, we might hypothesise that the HVP has probably not been overcome during childhood. In this case, the associated developmental transition hypothesis (Nunner-Winkler, 1993; Krettenauer, Malti, & Sokol, 2008) cannot be confirmed.

Moreover, the question arises to what extent the HVP emerges in later phases of moral development; and if so, what it might mean if even adults show patterns like HV, that is, feeling happy when breaking rules. Oser and Reichenbach (2005) pointed out that there might be other, complementary patterns of moral decision-making and emotion attributions. The authors emphasised that there are people who act in line with their deontic moral judgments and obey moral rules, but at the same time feel unhappy, for example, because they expect to suffer disadvantages compared to others who prefer to stick to their own needs in similar situations. Oser and Reichenbach call this pattern the “Unhappy Moralist” (UM). Other possible patterns are those of the Happy Moralist (HM) and the Unhappy Victimizer (UV) (Oser & Reichenbach, 2005).

Finally, former research indicated that the percentage of people applying patterns of moral decision-making like the HV varies depending on the quality of the conflict presented as well as on how the judgments were measured (Nunner-Winkler, 2013). To gain deeper insights into the conditions under which the different patterns emerge, this paper goes beyond a mere description of the patterns themselves and addresses whether and to what extent patterns of moral decision-making, in particular the HV, vary depending on situational determinants and procedures of measurement. According to Nunner-Winkler (2013), situational determinants can refer to (a) the type of (moral) judgment elicited; (b) the type of story (and conflict) presented; and (c) a combination of both.

In this paper, results from four empirical studies are presented. Some of the findings in studies 1, 3, and 4 have already been published in other contexts, but are discussed here from new angles. First, we introduce results on patterns of moral decision making and emotion attributions in adolescence (chapter 2) and adulthood (chapter 3). The aim is (a) to find out whether the HV and complementing patterns of moral decision-making and emotion attributions (re-)emerge after childhood; and (b) to ascertain that these patterns do not represent the original Happy Victimizer Phenomenon as identified in childhood. Second, we offer insights regarding situational determinants of patterns of moral-decision making and emotion attributions. Third, results and methodological limitations of the studies presented are critically discussed to stimulate further research and theory building (chapter 4). Finally, we introduce potential explanations of these patterns and provide first suggestions regarding the potential impact of the patterns on action and behaviour (chapter 5).

In this section, we present two recent studies investigating patterns of moral judgments, action decisions, emotion attributions and the respective justifications in adolescents following the Happy Victimizer tradition. A special focus lies on the role of situational cues and the way they (may) result in situation specific patterns of moral reasoning and decision-making. The study by Döring (2013) investigated the HV Pattern within a standardised, representative survey with children and adolescents in fourth, seventh and ninth grade. In a questionnaire, students were presented two situations designed as moral conflicts and asked to write down their moral decisions, reasons and emotions for each situation. In the study by Gutzwiller & Perren (2015, 2016) a qualitative, scenario-based measure was used requiring participants to give written answers to a situation involving a passive moral temptation.

The study by Döring (2013) was intended to explore to what extend the different patterns of moral decision-making, in particular the HV pattern, emerged; how these patterns could be explained in adolescence; and whether an ongoing linear growth of moral motivation could be observed. In an earlier study, Krettenauer (2011) had hypothesised an increase of moral motivation with age, because, firstly, children perceive values as external and, secondly, “individual conscience becomes more salient” with age (Krettenauer, 2011, p. 311). However, contrary to predictions, no increase of moral motivation had been found for students of seventh, ninth and eleventh grade (Krettenauer, 2011). Another study by Nunner-Winkler (2008) had revealed an age-related increase between childhood and early adulthood. However, that study had not included adolescents. Therefore, in the study by Döring (2013), a representative student sample was used to investigate the developmental pathway of moral motivation (as indicated by the proportion of Happy Victimizers) between late childhood and adolescence. We give a brief description of the methodology used and discuss some central results.

2.1.1 Method

A representative, standardised student survey was used to investigate children in the transition between childhood and adolescence. Students of fourth, N=1.221, M (SD) = 10.05 (0.45), seventh, N=815, M (SD) = 13.18 (0.54), and ninth grade, N=2.891, M (SD) = 15.18 (0.58) were asked to fill in a questionnaire on two moral conflicts. The first was a vignette with the following story: “Imagine you offered your bike for sale. You want to sell it for 400 Euros. A young man is interested. He bargains with you and you agree on 320 Euros. Then he says: `Sorry, I don’t have the money on me; I’ll quickly run home to get it. I’ll be back in half an hour.’ You say: ‘Agreed, I’ll wait for you.’ Shortly after he is gone, another customer shows up who is willing to pay the full price”. The second vignette was the following: “Imagine that you have found a purse with 100 Euros in it and an identity card of the owner” (Malti & Buchmann, 2010, p. 142). In this assessment, situational determinants referred to the use of two different stories and associated conflicts (breaking an oral contract vs. finding money that belongs to someone else). Subsequent to reading the two moral conflicts, participants were asked what they themselves would do in the described situation (action decision); why they would do it (reason); and how they would feel (emotion). If a participant decided to wait for the first customer because of moral reasons (e.g., “because I promised”) and reported positive emotions, s/he was categorised as Happy Moralist (HM). The Happy Victimizer (HV) category was used if a person decided to sell the bike to the second customer because of the money and felt good about that decision.

2.1.2 Results

Chi² tests were used to compare the percentage of HVs between age groups. For both moral conflicts the percentage of HVs was higher in ninth (27 % vs. 8.6 %) than in fourth grade (11.9 % vs. 8.7 %). Seventh grade results were not significantly different from ninth but from fourth grade (22.6 % vs. 8.7 %). Compared to the results for HV, the percentage of HM was higher in fourth than in ninth grade (Cramer’s V [bike-conflict] = .19, p<.001; Cramer’s V [money conflict] = .21, p<.001). Therefore, the results showed a decrease of moral motivation, that is, more participants being categorised as HVs in the adolescent than in the childhood subsample.

2.1.3 Discussion

The results are limited as the study was only cross-sectional and calls for replication in a longitudinal design. However, the results indicating a decrease of moral motivation are in line with research on identity development and the age crime curve (see Döring, 2013). Equally, some critical considerations regarding the assessment of the HV Pattern are necessary. First, Döring (2013) used two moral conflicts from earlier studies (Malti & Buchmann, 2010; Nunner-Winkler, Meyer-Nikele & Wohlrab, 2006) to assess the HV. However, the two moral conflicts were correlated at a low level only. One of the reasons for the low correlation might be that one conflict was not only between a moral rule and a personal need; the moral rule was also congruent with a judicial issue (money conflict), suggesting that situational cues played a role in the perception of the conflicts. This might have enhanced the perceived quality of the moral conflict, resulting in fewer adolescents showing the HV Pattern in that conflict. Also, the low correlation between the conflicts can be seen as an indication of situation specifity, that is, the specifics of a given moral conflict influencing its interpretation and the subsequent moral judgment.

A second issue is the importance of others for decision making. If it is possible that an immoral decision becomes public, fewer adolescents have positive emotions while making an immoral decision in an anonymous setting. Another possible explanation would be in line with motivational psychology: Motivation varies and is rather a state than a trait (cf. Vallerand, 2000). This explanation is underlined by the fact that moral motivation is only moderately (but significantly) correlated with moral identity and empathy (Döring, 2013). Regarding the relationship between moral motivation and violent behaviour, the analysis by Döring (2013) revealed a significant relationship even after controlling for other important predictors of violent deviant behaviour in a logistic regression model (e.g. sex, self-control, deviant peers, intrafamiliar violence), thus confirming earlier research.

Research within the Happy Victimizer Paradigm (HVP) has consistently made use of scenarios (vignettes) of moral or morally relevant situations to assess children’s, and more recently, adolescents’ and adults’, moral reasoning (e.g., Nunner-Winkler, 2007). Scenarios have mostly involved proactive, obvious transgressions of moral rules (e.g., stealing, hitting, excluding someone, etc.) where the protagonist intentionally displays behaviours harming others (e.g., Nunner-Winkler & Sodian, 1988). Until very recently, passive moral temptations where a protagonist does not intend to transgress and only realises that s/he might do so as a result of specific circumstances (Gutzwiller-Helfenfinger & Perren, 2015; 2016; Heinrichs et al., 2015) do not seem to have been investigated. Thus, getting too much change money, the situation used in our study, differs dramatically from proactively stealing money from someone. The former situation is more ambiguous and open, especially as it is not directly related to a negative duty, like, for example “thou shalt not steal”, which clearly applies to the latter. At best, it may be related to positive duties like “you should help someone in need”; and even then, the realisation that a shop assistant ending up with a negative balance can be seen as a person in need does not come easily. As negative duties carry a stronger moral obligation than positive duties (e.g., Belliotti, 1981), this adds to the ambiguity of the situation.

Scenarios measures used within the HVP often describe a transgression as “fait accompli” and do not require participants to make deontic judgments, that is, they do not leave the situation open and ask what the protagonist should do. However, including a deontic judgment makes it possible to assess participants’ initial constructions of a given moral or morally relevant situation and to gain insight into the features of the situation that are both salient and relevant to them (cf. Wainryb, Brehl, & Matwin, 2005). Still, asking for a deontic judgment (“What should X [the protagonist] do”) does not necessarily represent the course of action chosen for oneself. Therefore, it is necessary to include both a deontic judgment and own action decision in addition to a judgment of the hypothetical transgression itself (“X kept the money. Is it okay or not to keep the money”) to have a fuller representation of participants’ construction of the situation. The different judgment conditions can thus be conceptualised as situational variations (cf. Nunner-Winkler, 2013). Accordingly, the reasoning patterns resulting from the different moral judgments need to be considered in order to have a fuller understanding of adolescents’ moral meaning-making.

In this study, adolescents’ moral reasoning was investigated as part of a prospective longitudinal study on teens’ use of electronic devices and social media and its relation to social behaviour (netTEEN; e.g., Sticca, Ruggieri, Alsaker, & Perren, 2013). In this chapter the moral reasoning patterns of adolescents responding to a passive moral temptation scenario are explored. One question of particular interest is whether we will find participants actually saying that one should / they would keep the money (self-perspective) or that keeping the money would be okay (other perspective), respectively. Based on earlier research within the Happy Victimizer Paradigm, even very young children display moral rule knowledge by saying that stealing etc. is not okay. However, the ambiguity of the situation in the present scenario might make it less clear for participants to perceive the moral obligation included. Both the theoretical rationale and the findings presented here have not been published so far.

2.2.1 Method

331 14-year-old Swiss secondary I students (48% male) from 25 classrooms participated in the study, which included four assessment points within 2 years. Data from t4 are presented.

Data collection took part in a classroom setting. Students gave written answers to open-ended questions in a scenario involving a passive moral temptation (“Change Money”) with a protagonist buying a bicycle light in a shop and receiving too much change money (10 Swiss Francs).

Participants had to make three different moral judgments: (a) a deontic judgment on what the protagonist should do (keep the money, give back the money or both), justify their judgment, attribute (an) emotion(s) to the protagonist and justify their attribution(s) (deontic); (b) indicate what they themselves would do in the given situation (keep the money, give back the money or both; self-judgment), justify their decision, attribute (an) emotion(s) to themselves, and justify their attribution(s); and (c) after being told that the protagonist had transgressed the moral rule (i.e., kept the excess change) to judge the transgression (okay or not okay or both), justify their judgment, attribute (an) emotion(s) to the protagonist, and justify their attribution(s) ( “classical” Happy Victimizer condition). Emotion attributions consisted of a response scale (happy, proud, indifferent, sad, angry, anxious, ashamed), with students marking the correct response (cf. Malti, Gasser, & Buchmann, 2009).

Justifications of judgments and emotion attributions were content analysed using categories from research within the Happy Victimizer Paradigm and research on moral disengagement. The coding process included deductive coding based on existing categorisations (e.g., Bandura, Barbaranelli, Caprara, & Pastorelli, 1996; Gutzwiller-Helfenfinger, 2009; Menesini, Sanchez, Fonzi, Ortega, Costabile, & Lo Feudo, 2003) and inductive and abductive coding leading to the development of new or extensions of existing categories (e.g., Perren & Gutzwiller-Helfenfinger, 2012). Justifications were coded by two well-trained coders who were blind to the other data of the study. Inter-rater reliability (18% of scenarios) was high (percentage of perfect agreement = .88).

2.2.2 Results

For all moral judgments (deontic, self, transgression), almost no one chose the “both” categories representing a state of indecision. Therefore, the “both” categories were excluded from further analyses.

In a first step, frequencies regarding judgments and emotion attributions were analysed. Regarding morally appropriate judgments (in terms of following a moral rule and thereby not harming another’s rights or welfare), roughly three quarters of participants said that Jan/a should give the money back (76.1 %), that they themselves would give it back (76.1%), and that it was not okay that Jan/a kept the money (71.9%). Of those who said that Jan/a should give the money back, 79.1% attributed positive and 11.6% negative emotions, while 9.2% attributed indifference to Jan/a. Of those who said that they themselves would give the money back, 72.5% attributed positive and 14.2% attributed negative emotions, whereas 13.3% attributed indifference to themselves. Of those who said that it was not okay that Jan/a kept the money, 15.3% attributed positive and 68.2% attributed negative emotions, while 16.5% attributed indifference to Jan/a. Overall, 36 (10.9%) participants could be identified as displaying the “classical” Happy Victimizer Pattern, that is, judging the hypothetical protagonist’s transgression as wrong while attributing positive emotions to the transgressor. The predominant justification of the positive emotion attributed was hedonism, mostly relating to Jan/a’s having more money now, being used by 19 (52.8%) participants (out of a total of 36 participants).

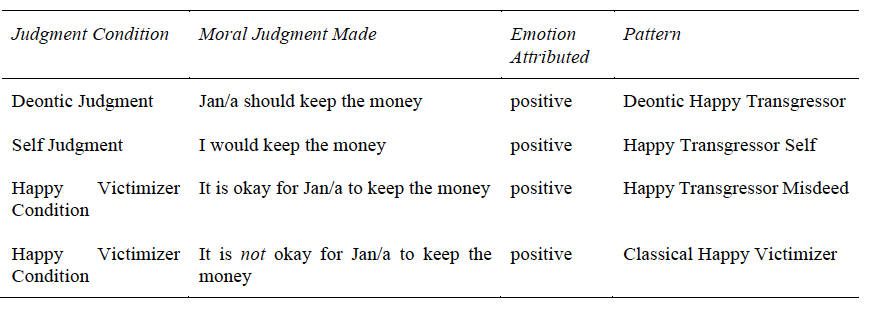

Regarding the counterpart, that is, morally inappropriate judgments (in favour of breaking the moral rule and thereby harming another’s rights or welfare), roughly a quarter of participants said that Jan/a should keep the money (23.9%), that they themselves would keep the money (23.9%), and that it was okay that Jan/a kept the money (24.9%). Of those who said that Jan/a should keep the money 70.5% attributed positive and 5.1% attributed negative emotions, whereas 24.4 attributed indifference to Jan/a. Of those who said that they themselves would keep the money, 54.5% attributed positive and 9.1% attributed negative emotions, whereas 36.4% attributed indifference to themselves. Of those who said that it was okay that Jan/a kept the money, 64.1% attributed positive and 6.4% attributed negative emotions, while 29.5% attributed indifference to Jan/a. Participants displayed also a “new” Victimizer Reasoning Pattern, that we call “Happy Transgressor” (okay to keep the money and positive emotions; cf. Latzko & Gutzwiller-Helfenfinger, 2014) to distinguish it from the classical Happy Victimizer Pattern (see Table 1). Overall, 44 (13.3%) participants displayed this reasoning pattern in the deontic judgment (Deontic Happy Transgressor: “S/he should keep the money and would feel good about it”); 42 (12.7%) did so when indicating what they themselves would do in the given situation (Happy Transgressor Self: “I would keep the money and feel good about it”); and 50 (15.1%) when judging the rule transgression (Happy Transgressor Misdeed: “It is okay for him/her to keep the money, and s/he feels good about it”).

The predominant justification of the positive emotions attributed was again hedonism, relating to Jan/a or oneself having more money now: For the Deontic Happy Transgressor, 28 (63.4%) participants (out of a total of 44), for the Happy Transgressor Self, 25 (59.5%) participants (out of a total of 42), and for the Happy Transgressor Misdeed, 30 (60%) participants (out of a total of 50) gave hedonistic justifications.

Table 1

The Happy Transgressor Patterns and the Classical Happy Victimizer Pattern in the “Change” Vignette

Second, to investigate the relationship between the use of the classical Happy Victimizer Pattern and the new Transgressor Reasoning Patterns, crosstabulations were calculated. A significant relationship between reasoning patterns was found for: Deontic Happy Transgressor with Happy Transgressor Self, Χ2(1, 331) = 177.84, p = .000, with 33 participants using both patterns; Deontic Happy Transgressor with Happy Transgressor Misdeed, Χ2 (1, 331) = 152.93, p = .000, with 34 participants using both patterns; and Happy Transgressor Self with Happy Transgressor Misdeed, Χ2 (1, 331) = 162.64, p = .000, with 34 participants using both patterns. No relationship was found between the Happy Transgressor patterns (Deontic and Self) and the classical Happy Victimizer pattern. The Happy Transgressor Misdeed and the classical Happy Victimizer pattern are mutually exclusive, making analyses regarding their relationship superfluous. When the total use of immoral reasoning patterns was considered, we found that 234 (70.7%) of participants did not use any of the patterns, while 53 (16%) used one, 13 (3.9%) used two, and 31 (9.4%) used three patterns.

2.2.3 Discussion

Using a passive moral temptation scenario, the moral reasoning patterns of adolescents judging a vignette where a protagonist (Jan/a) gets too much money back were explored. About three quarters of participants made morally appropriate judgments and mostly attributed compatible emotions, saying that Jan/a should give the money back and would feel good doing so, that they themselves would give the money back and feel good doing so, and that it was not okay if Jan/a kept the money and that she would feel bad. Still, about a quarter of participants made morally inappropriate judgments, actually saying that Jan/a should keep the money, that they themselves would keep the money, and that it was okay that Jan/a kept the money. Emotions attributed were mostly positive, indifference was attributed in roughly a quarter or a third of the cases, while negative emotions were least frequently attributed. This is a surprisingly high proportion of morally inappropriate judgments made in favour of transgressing in combination with predominantly positive emotions (cf. Heinrichs et al., 2015). A possible explanation lies in the nature of the scenario chosen: The passive nature of the moral temptation (with the protagonist not intending to transgress and being thrown into the situation) in combination with the inclusion of a positive duty (helping someone in need or giving back what is not one’s property) might have led these participants to construct the basic situation (receiving too much change) as being not or only weakly related to moral rules.

The picture becomes more distinct when we consider the Happy Victimizer and the Happy Transgressor patterns. Between one tenth and one sixth of participants displayed one of these reasoning patterns: the classical Happy Victimizer (it is not okay that Jan/a kept the money but s/he felt good doing so), Deontic Happy Transgressor (one should keep the money and would feel good doing so), Happy Transgressor Self (participants would keep the money and feel good doing so), and Happy Transgressor Misdeed (it is okay that Jan/a kept the money and s/he felt good doing so). The predominant justification given for the attribution of positive emotions within all patterns was hedonism, mostly referring to the fact that oneself or Jan/a now had more money. Thus, it seems that having more money as a result of the shop assistant’s error when one did not intend to transgress in the first place was the salient and relevant construction for these participants.

We argue that judging what Jan/a should do versus what oneself would do versus judging whether it is okay that Jan/a kept the money represent different situations or at least situational variations. Actually, the differentiation between other-as-perpetrator and self-as-perpetrator (e.g., Keller, Lourenço, Malti, & Saalbach, 2003) was an important milestone in the research on moral motivation (e.g., Gasser et al., 2013). Moral reasoning in the context of self-as-perpetrator is seen as representing higher self-relevance and therefore a more valid indicator of moral motivation in terms of giving priority to moral over non-moral values or solutions. Accordingly, it is important to investigate the relationship between the patterns. Our results indicate that there were meaningful bivariate relationships between the three Happy Transgressor patterns, suggesting a relative stability in the use of at least two of them. Conversely, no relationship was found between the Deontic or Self Happy Transgressor patterns and the classical Happy Victimizer pattern. It seems that making meaning of the scenario when everything is still open (What should Jan/a do? What would you do?) differs from judging the transgression by Jan/a (a hypothetical perpetrator) as a given fact. That self-as-perpetrator (Happy Transgressor Self) is associated with other-as-perpetrator for the Deontic Happy Transgressor but not for the classical Happy Victimizer confirms the potential crucial role of the openness of the situation, that is, before the transgression is introduced. Judgments of the transgression alone offer only limited insights into individuals’ construction and interpretation of a situation. This underlines the importance of studying a wider array of moral reasoning patterns in order to gain a deeper insight into adolescents’ moral meaning-making.

The results presented suggest that it is important to move beyond the Happy Victimizer Pattern to understand adolescents’ (and potentially adults’) moral reasoning and to include not only judgments and emotion attributions (and justifications) relating to a rule transgression but also deontic and self judgments in situations including a moral temptation.

In the previous section results on moral decision-making in adolescence confirmed that, contrary to previous assumptions based on conceptions of the HVP as a developmental transition in early childhood, not all teenagers leave Happy Victimizing behind. However, earlier studies indicated that the HV or similar structures emerge in adulthood, too, but mainly among people showing deviant behaviour (Krettenauer, Asendorpf & Nunner-Winkler, 2013; Nunner-Winkler, 2013). Moreover, experimental studies where participants play dictator games reveal that a relevant percentage of adults take choices that benefit themselves to the detriment of their fellow players. Only about 20 percent share in a fair manner (50/50 split) in the standard condition (Fehr & Schmidt, 2006; Forsythe, Horowitz, Savin, & Sefton, 1994). Research about team work also confirmed that free riders (people who accept or even intend to benefit from the work of a group while contributing less themselves) are quite common (Dingel, Wei, & Huq, 2013). Whether unfair intentions or behaviour are punished or whether selfish behaviour is accepted even in the case of inequality seems to depend on situational cues (Fehr & Schmidt, 1999). Thus, it is an open question to what extent patterns resembling the HV may appear in adulthood and how they are connected to deviant behaviour. Furthermore, the studies on free riding or sharing mentioned above may point to the fact that “deviant” behaviour is not limited to situations of high moral intensity like moral dilemmas, but rather begins in situations of low moral intensity. Some kinds of “deviant” behaviour or moral transgressions seem to be widely spread and accepted as “normal”, like for example violating speed limits, tax fraud, white lies or – particularly in some cultural contexts – corruption. Maybe we have to acknowledge that some kinds of “immoral behaviour” are to some extent omnipresent in adults’ everday life. Therefore, it seems to be fruitful to investigate the HV in adulthood to disentangle the various facets of moral functioning. In particular, we want to study how situational cues relating to different contexts cause intrapersonal variations of moral reasoning as well as emotion attributions and to address the impact of measurement methods on the identification of the HV in adulthood.

3.1.1 Method

In this study 271 students of economics and business education filled in paper-and-pencil questionnaires. They were confronted with four different situations, all assumed to provoke patterns of moral decision-making and embedded in an economically relevant context: Buying a new TV set as a private consumer (TV Sale), making a difficult decision as an entrepreneur of a newly founded start-up (Start-up), being tempted while getting too much change when buying something in a tourist shop (Change), or asking for a refund of (unwarranted) traveling expenses from one’s company (Travel Costs). Participants were asked to decide between two alternative courses of action and to reason why they would choose this alternative if they had to act themselves (self judgment; condition [b] in study 2, see section 2.1.1) as well as to state how they would feel (from “good” to “bad” on a four-point Likert scale). The participants were coded as displaying the HV if they decided in favour of the transgression and attributed good or rather good emotions; as Unhappy Victimizers (UV) if they opted for the transgression and attributed rather bad or bad emotions; as Happy Moralists (HM) if they opted for obeying the rule and attributed good or rather good emotions; and as Unhappy Moralists (UM) if they decided for obeying the rule and attributed rather bad or bad emotions.

3.1.2 Results

Among the 271 participants we found varying proportions of HV patterns across the four situations: from 31.1% percent (“Start-up”), 36.6 % (“TV Sale”) and 41.3 % (“Travel Costs”) up to 49.2% (“Change”). Also, the amount of HM patterns differed across situations: from 35.4% (“Change”) to 47.2 (“TV Sale” and “Travel Costs”) up to 61.8% (“Start-up”). The “Change” situation elicited the highest proportion of decisions towards victimizing (UV and HV: 63%), the Start-up situation elicited the lowest proportion of victimizing stragegies (UV and HV: 34.7%) (for more details see Heinrichs et al., 2015).

Moreover, we did not observe strong correlations between the situational ratings, which points to substantial intra-individual variation across situations (see also study 1 above). Because of the nominal level of measurement we calculated the Pearson’s Contingency Coefficient C as well as Cramer’s V on a subsample of those cases where the agency type could be identified for all four situations (n = 254). The Monte Carlo method was used because some cells had fewer than five cases.

Table 2

Cramer’s V and Contingency Coefficient C for all Four Agency Types (HV, UV, HM, UM) Across the Four Situations

i) These results have already been published in German (see

Heinrichs et al., 2015), but in this paper, they are discussed

compared to the results towards the HV in adolescence (study 1

and 2). ii) *** refers to p < 0.001, ** to p < 0.01 and *

to p < 0.05.

In three out of six possible comparisons we found weak, but significant indicators of consistency (see Table 2).

3.1.3 Discussion

All in all, the results confirm that up to 63% of the participants intended to trangsgress moral rules at least in certain situations and up to 49.2% would feel good or rather good to do so. Thus, these findings clearly point out that Happy Victimizing emerged in adulthood, too, and seemed to be quite common. However, we did not observe strong correlations between the situational ratings, which points to substantial intra-individual variation across situations (see also study 1 above). It seems that the emergence of these patterns depended on the stimulating situation. Thus, patterns of moral decisions making did not show interpersonal consitency across situations. However, these results are limited to situations embedded in economic contexts and therefore mainly point to negative financial consequences for other persons or a company. Similar to study 2, the situations include some forms of temptation rather than systematically planned deviant behaviour. It is possible that the patterns of moral reasoning might change if other situational contexts like for example contexts of prosocialness are used or if bodily or psychological harm to the victims is included.

3.2.1 Method

Study 4 explores how the patterns of moral reasoning and emotion attributions differ depending on the kind of moral judgment elicited: deontic judgment (“What should the protagonist do?”), self judgment (“What would you do?”), classical HV condition (rating whether a transgression already committed by the protagonist is okay or not okay).

Study 4 included a paper-and-pencil survey requiring students of economics and business education (N=233) to rate two different situations, both potentially provoking moral transgressions. One situation referred to the context of a start-up enterprise (see study 3, in section 3.1), the other was a slighty adapted version of the “Change Money” vignette used in Study 2 (the classmate was replaced by a colleague, see section 2.2). As in study 2 participants had to make different moral judgments and attribute emotions for both situations. They were asked to make their decisions from three different perspectives: deontic judgment, self judgment, and classical Happy Victimizer condition. Accordingly, study 4 explored situational variations in moral reasoning patterns relating to decision perspective and situational variations (“Start-up” and “Change Money”). In addition to their decisions, the participants had to indicate how the protagonist (i.e., in the deontic judgment and the classical HV condition) or they themselves (self judgment condition) would feel if they acted as they decided. They had to rate emotions on a 4-point Likert scale ranging from good (1) to bad (4). Ratings of 1 and 2 were coded as happy, 3 and 4 as unhappy. Additionally, we differed between degrees of HV reasoning patterns: if positive emotions were attributed, the «pure» HV was assigned; if rather positive emotions were attributed, the «moderate» HV was assigned.

3.2.2 Results

For our analyses, we were interested in the cases where participants basically argued in favour of the transgression, that is, said that the protagonist should transgress (deontic judgment), that they themselves would transgress (self judgment), and that it was okay that the protagonist had transgressed (classical HV condition). Accordingly, the classical HV pattern where participants said that it was not okay that the protagonist had transgressed (e.g., kept the change money) but felt good about it was not included in our analyses. When using the classical HV condition, we found that 35.4 % of the participants said that the transgression was “o.k.” in the Start-up-Story, and 77.3 % did so in the Change-Money-Story. However, among those only 9 out of 233 (4 %) attributed positive or rather positive emotions in the Start-up-Story thus displaying a a pattern corresponding to the Happy Transgressor Misdeed in study 2 (see Table 1). In the “Change Money” vignette 31 out of 220 (14.1%) participants displayed this pattern. In contrast, when asking what the participants would do (self judgment) the proportion of participants preferring the transgression was higher in the Start-up-Story (n=107; 46.9 %) than in the Change Money-Story (n=30; 13.6%). When including emotion attributions, the number of transgression-friendly patterns (corresponding to the Happy Transgressor Self in study 2) was as follows: In the start-up context 67 out of 228 students (29.4%) displayed the pattern, in the Change Money-Story 22 out of 220 (10.0%) did so. The picture regarding transgression-friendly patterns in the deontic judgment condition was similar to that displayed in the self judgment condition: Among the adult participants of study 4, the number of participants deciding in favour of the transgression in the deontic condition was 126 (54.3%) in the Start-up-Story and 29 (12.8%) in the Change Money-Story. When including emotion attributions, 67 out of 126 (28.9%) participants in the Start-up-Story and 20 out of 29 (8.9%) in the Change Money-Story attributed positive or rather positive emotions and thus displayed a pattern corresponding to the Deontic Happy Transgressor pattern in study 2.

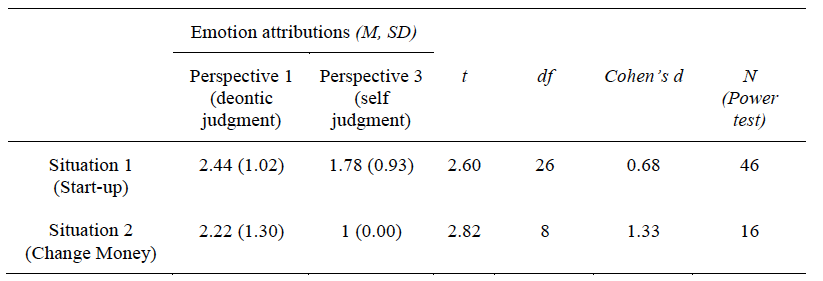

Table 3

Mean Differences for Deontic and Self judgment Across Situations (T-tests; p>0.005)

To gain deeper insights into potential differences in emotions attributions between the various reasoning patterns in the three conditions (deontic judgment, self judgment, classical HV condition), paired samples T-tests were performed. This enabled us to study whether the means of the emotions attributed (1: good to 4: bad) of those persons who preferred to transgress the rule (i.e., victimise) differed significantly from the means of those who preferred not to transgress the rule (i.e., moralise) (Bonferroni correction included). Results showed no significant differences between deontic judgment and the self judgment, or the deontic judgment and the classical HV condition. However, contrasting the victimisers’ emotion attributions between the deontic judgment (“one should break the rule”) and the self judgment (“I would break the rule”) middle to high effect sizes were found (Start-up: d = 0.68; Change Money: d = 1.33). Conducting a priori power analyses revealed that the mean differences would have been significant in the Start-up situation if the sample had been larger than 46 and in the Change Money if the sample had been larger than 16, respectively (see Table 3). Moreover, T-tests for comparing victimising in the classical HV condition (Happy Transgressor Misdeed) with victimising in the self judgment (Happy Transgressor Self) confirmed that significantly more negative (i.e., morally appropriate) emotions were attributed to the perpetrator in the classical HV condition (Happy Transgressor Misdeed) than in the self judgment condition (Happy Transgressor Self; Start-Up: t = 11.90, df = 64; p < 0.0001; Change Money: t = 22.30, df = 154; p < 0.0001).

3.2.3 Discussion

First of all, in study 4, the number of participants displaying the HV pattern differs between the Start-up and the Change Money story. In this regard, these results confirm previous findings of situation specificity of moral reasoning. Considering the results in more detail, we see that in the classical condition there are less HV Patterns in the Start-up situation than in the Change Money story. In contrast, in regard to deontic and self judgments we found more people preferring victimising in the Start-up situation than in the Change Money story. A similar picture occurs among all participants preferring victimizing as well as in the subgroup of those who preferred victimizing and feel happy. Thus, both situational cues of the stories as well as the method of measuring the decision towards obeying or breaking the moral rule seem to impact moral judging and emotion attributions. In the classical condition high rates of Victimizing Patterns emerged, but the judgments of most of the participants who preferred transgressing attributed bad or rather bad emotions and insofar the patterns have to be coded as UV. Maybe attributing negative emotions to another’s transgression indicates that, if the participants have to act by themselves, they would switch from breaking to preferring to obey the moral rule and – hopefully – would feel good about it. This needs to be addressed in future research. However, maybe, these results are more a consequence of the measurement approach used than an indication of specific moral functioning. Participants had to retrospectively rate another person’s behaviour that had already been enacted. The question arises whether this method of projection works better for children than adults who normally are able to take another person’s perspective. Altogether, the results suggest interaction effects between stories and methods of measurement. And they encourage us to differ between types of patterns – as related to a given story and method of measurement (associated prompts)– as was done in study 2 (Deontic Happy Transgressor, Happy Transgressor Self, Happy Transgeressor Misdeed, Classical Happy Victimizer) and to develop hypotheses about the relevance and meaning of these patterns of moral decision-making and emotion attributions among adults.

One direction to continue is to think about the relevance of the Happy Victimizer and Happy Transgressor Patterns for acting. In study 4, we found that emotion attributions of those participants who favoured the transgression differed according to situational stimuli (Start-up story vs. Change Money story). The rate of Happy Victimizer and Transgressor Patterns obviously varied depending on the the way the decision was measured. Regarding the deontic and the self judgment conditions – both referring to decisions about fictive actions or action in the future – more participants showed transgression-friendly patterns than in the classical condition. Moreover, the findings indicate – in line with results for children (Keller et al., 2003; Nunner-Winkler, 2013) that self judgments go together with more positive emotions than deontic judgments. This seems to be plausible if we assume that self judgments represent intentions to act that include a self commitment towards one way of acting, maybe after having struggled with ambivalence or even inner conflicts (see Heinrichs, Kärner & Reinke, this issue).

Four limitations are discussed relating to both the studies presented and the state of the art of research on the HV in adolescence and adulthood.

Former research has already pointed out that the percentage of individuals identified as displaying the HV varies depending on the methods used to assess patterns of moral decision-making as well as of emotion attributions. In particular, different results emerged if participants were asked to decide what the protagonist in an open-ended story should do (other-perspective) or what he or she himself would do (self-perspective) in that situation (Nunner-Winkler, 2013). Nunner-Winkler and colleagues originally used stories already including a transgression by a protagonist and asked children to judge that action. This method of projection seems to work well with children at the age of 4. Children at that age are assumed not to be able to differ between their own and others’ perspectives (Barden et al., 1980). However, there are serious doubts whether this method can be applied in adolescence (see 2.2) or adulthood (see 3.2). Older participants in our own pilot interview studies came up with comments clearly indicating that they could not simply impose their own decisions and emotions upon the protagonist. Moreover, they pointed out that they could not imagine how the protagonist felt because they were not that person and therefore did not know the protagonist’s thoughts or feelings. Especially the results of study 2 showed that different moral judgments involving different perspectives yielded differential reasoning patterns in adolescents, some of them not described previously (the Happy Transgressor Patterns, see chapter 2.2.2; see also Gutzwiller-Helfenfinger & Latzko, this issue). Therefore, our results confirm that self and other perspectives need to be included when studying the moral reasoning patterns of adolescents and adults. Moreover, in particular the categories suggested in study 2 represent four types of patterns of moral decision-making and related emotion attributios in morally relevant situations. The three new Happy Transgressor patterns need to be studied more deeply.

In all our studies we used questionnaires with standardised and half-standardised questions. Standardised questions were used for basic judgments (deontic, action decision, transgression, emotion attribution), while open-ended questions were used to gain insights into participants’ reasoning about these judgments and attributions. However, in studies 3 and 4 participants often gave quite short answers, making content analyses difficult. Thus, it might be fruitful to conduct mixed-methods and experimental studies which allow for a more sensitive and multi-variant assessment of moral reasoning patterns while at the same time making the inclusion of larger samples possible. As we started studying the HV in adulthood, we conducted interviews and later moved on to questionnaires to investigate the context sensitivity of HV. We confirmed that HV varies intra-individually across situations. Therefore, it might be interesting to again conduct interviews as part of mixed-methods studies to gain deeper insights into the way participants reason regarding judgments, courses of action, and emotion attributions, in particular, to explore the meaning participants make for the different categories as Deontic Happy Transgressor, Happy Transgressor Self, Happy Transgressor Misdeed and Classical Happy Victimizer.

As discussed above, some of our results indicate that there are people who agree on the morally inadequate solution independent of the procedure of measurement: They claim that the protagonist should break the rule; they confirm that they themselves would also transgress; and they assess the transgression as being okay. They argue consistently in favour of the transgression. Maybe they would also act accordingly in real life. However, asking for judgments, intentions or action decisions via questionnaires and interviews using hypothetical scenarios has rather low external validity when it comes to predicting moral behaviour. Moreover, within HV research, issues of social desirability have been frequently raised and critically discussed. In the context of questionnaires and interviews using participants’ self-reported judgments, we only assess what participants tell the researchers what they would do and how they judge certain ways of acting, but we do not know what they really would do if they experienced similar situations in real life. Moreover, in our studies motivation, volition, and emotions were not assessed directly, but inferred from self-reports. It is important to find creative ways of investigating the impact of the identified patterns of moral decision-making on actual behaviour. As already mentioned, an experimental approach including the systematic variation of situational cues and conditions may prove promising. Such an approach has been used in past studies on the HVP in children (e.g., Nunner-Winkler & Sodian, 1988).

The findings from our studies clearly show that patterns of moral decision-making and emotion attributions do vary among adolescents and adults due to situational determinants. Thus, the HVP can no longer be interpreted as a developmental stage that will be overcome during childhood. This is an important step for this field of research; and there are many options how to move further ahead and make theoretical as well as empirical progress (Lakatos, 1978).

First, there is a lack of research how to explain the finding that differential types of moral decision-making and emotion attributions emerge across situations, indicating intra-individual variation. The remaining papers in this special issue present theoretical approaches that represent differential theoretical perspectives reflecting whether patterns of moral deicsion-making reflect emotional (moral) development, specific cognitive structures, or are dependent on volitional processes or intentions.

Second, our findings confirm that patterns of moral decision-making depend on situational cues. However, the data presented call for deeper investigations of the kind of situational factors that contribute to individuals’ changes regarding judgments, decisions, and emotion attributions across situations. Earlier studies for example pointed out that being treated unfairly or having a position differing from that of a relevant other may cause changes in moral decision-making (Heinrichs et al., 2015). Additional factors influencing the interpretation of morally relevant situations, like for example personal determinants, need to be considered in order to gain a fuller picture of the stability versus change in adolescents’ and adults moral reasoning patterns.

Third, there is a lack of longitudinal research to explore the relative contribution of developmental changes, personal determinants, and situational and contextual factors. Accordingly, variables like metacognitive capacities, attribution styles (Weiner, 2013), the moral self (Krettenauer, 2011), or moral climate need to be included in future prospective longitudinal research.

Fourth, if we assume that people prefer to have positive feelings, and that negative feelings might indicate unfulfilled needs or inner conflicts, it will also be interesting to study changes from patterns including the attribution of negative emotions towards patterns associated with positive emotions. Possibly, the attribution of negative emotions points to a motivation to change personal or situational determinants, maybe for individual development.

Finally, research on the HV and other patterns of moral decision-making faces the challenge of confirming whether these patterns of moral decision-making identified in the context of interviews and paper-and-pencil questionnaires are of high external validity and relevant for acting in everyday life (Heinrichs et al., this issue; Minnameier, this issue). Therefore, an interdisciplinary perspective on research on moral decision-making and the HV should be fostered, requiring a cooperation for example between psychologists, educationalists, economists, sociologists, and philosophers. Moreover, the HV could be investigated in a variety of contexts and domains of everyday (working) life to further explore similarities and differences in moral reasoning patterns across contexts and domains (see e.g., Heinrichs & Wuttke, 2016; Minnameier, Heinrichs, & Kirschbaum, 2016).

The question raised at the beginning, namely whether the HVP, originally identified in early childhood, at least diminishes during adolescence, focused on a developmental perspective. This starting point is relevant particularly in and for education. To discuss the implications of these results with respect to education requires us to raise both normative and empirical issues. Regarding normative issues, the question arises what patterns of moral decision-making should be aimed at in educational contexts. Parche-Kawik (2003) analysed theoretical approaches in organisational theory, business ethics, and education, and found that they include the assumption that individuals are or ought to be able to argue on Kohlberg’s stages five or six in morally relevant conflicts. However, other authors (e.g. Beck 2016, Minnameier, 2018; this issue) argue that acting to one’s own advantage is not only quite common, but also an appropriate way of acting if the established rules work as “moral institutions”. Moreover, the HV is claimed to represent one possible way of cooperation and of implementing moral ways of acting (Minnameier et al., 2016; Pies, 2009). Thus, apart from the empirical question how people reason in real-life moral conflicts, there is also the need for an intensive discussion on the normative question regarding the kind of argumentation that is adequate with respect to moral functioning and education.

We are grateful that Matthias Guerts provided substantial contributions to the analyses of Study 4 within his Bachelor’s Thesis at the Goethe-University Frankfurt/Main, Germany. We are also grateful for Julia Vogel’s and Carmen Amrein’s substantial contribution to analyses in Study 2 within a Bachelor’s (Julia Vogel) and a Master’s Thesis (Carmen Amrein) at the University of Teacher Education of Lucerne, Switzerland. Qualitative analyses in Study 2 were co-funded by the University of Teacher Education of Lucerne, Switzerland.

Andreoni, J., & Bernheim, B. D. (2009). Social image and the

50–50 norm: A theoretical and experimental analysis of audience

effects. Econometrica, 77, 1607-1636.

https://doi.org/10.3982/ECTA7384

Anesi, V. (2009). Moral hazard and free riding in collective

action. Social Choice and Welfare, 32(2),

197-219. doi: 10.1007/s00355-008-0318-8

Baier, K. (1965). The moral point of view. New York:

Random House.

Bandura, A., Barbaranelli, C., Caprara, G. V., & Pastorelli,

C. (1996). Mechanisms of moral disengagement in the exercise of

moral agency. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology,

71, 364-374. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.71.2.364

Barden, R. C., Zelko, F. A., Duncan, S. W. & Master, J. C.

(1980). Children’s consensual knowledge about the experimental

determinants of emotion. Journal of Personality and Social

Psychology, 39, 968-976.

https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.39.5.968

Beck, K. (2016). Individuelle Moral und Beruf: Eine

Integrationsaufgabe für die Ordnungsethik? [Individudal morality

and profession: An integrative task for Ordnungsethik?] In G.

Minnameier (Hrsg.), Ethik und Beruf: Interdisziplinäre

Zugänge (S. 41-54). Bielefeld: W. Bertelsmann Verlag.

Belliotti, R. A. (1981). Positive and negative duties. Theoria,

47 (2), 82-92.

Bretherton, I., Fritz, J., Zahn-Waxler, C., & Ridgeway, D.

(1986). Learning to talk about emotions: a functionalist

perspective. Child Development, 57, 529-548. doi:

10.2307/1130334

Dana, J., Weber, R. A., & Kuang, J. X. (2007). Exploiting

moral wiggle room: experiments demonstrating an illusory

preference for fairness. Economic Theory, 33(1), 67-80.

doi: 10.1007/s00199-006-0153-z

Dingel, M.J., Wei, W. & Huq, A. (2013). Cooperative learning

and peer evaluation: The effect of free riders on team performance

and the relationship between course performance and peer

evaluation. Journal of the Scholarship of Teaching and

Learning, 13(1), 45-56.

Döring, B. (2013). The development of moral identity and moral

motivation in childhood and adolescence. In K. Heinrichs, F. Oser

& T. Lovat (Eds.), Handbook of moral motivation.

Theories, models, applications (pp. 289-307). Rotterdam:

Sense Publishers.

Fehr, E., & Schmidt, K. M. (1999). A theory of fairness,

competition, and cooperation. The Quarterly Journal of

Economics, 114, 817-868.

https://doi.org/10.1162/003355399556151

Fehr, E. & Schmidt, K. (2006). The economics of fairness,

reciprocity and altruism – Experimental evidence and new theories.

In S.-C. Kolm & J. M. Ythier (Eds.), Handbook of the

economics of giving, altruism and reciprocity (pp.

615-691). Amsterdam: Elsevier.

https://doi.org/10.1016/S1574-0714(06)01008-6

Gasser, L., Gutzwiller-Helfenfinger, E., Latzko, B., & Malti,

T. (2013). Do moral emotion attributions motivate moral action? A

selective review of the literature. In K. Heinrichs, T. Lovat,

& F. Oser (Eds.),Handbook of moral motivation. Theories,

models, applications (pp. 307-322). Rotterdam: Sense

Publishers.

Gert, (2012). The definition of morality. In E. N. Zalta (Ed.), The

Stanford encyclopedia of philosophy (fall edition).

[http://plato.stanford.edu/archives/fall2012/entries/morality-definition/]

Gibbs, J. C. (2003). Moral development and reality.

Thousand Oaks etc.: Sage.

Gutzwiller-Helfenfinger, E. (2009). Moral Disengagement bei

Jugendlichen. Kodiermanual zur Auswertung des Fragebogens zum

moralischen Verständnis . [Moral disengagement in

adolescents. Coding manual for a moral understanding

questionnaire]. Unpublished manual. Teacher Training University of

Lucerne, Switzerland.

Gutzwiller-Helfenfinger, E. (2015). Not unlearning to care –

healthy moral development as a precondition for Nonkilling. In R.

Bahtijaragic Bach & J. E. Pim (Eds.), Nonkilling Balkans

(pp. 139-169). Sarajevo: University of Sarajevo, Faculty of

Philosophy & Honolulu: Center for Global Nonkilling.

Gutzwiller-Helfenfinger, E., & Latzko, B. (2020). Happy

Victimizing in emerging adulthood: Reconstruction of a

developmental phenomenon? Frontline Learning Research, 8(5),

47-69. https://doi.org/10.14786/flr.v8i5.382

Gutzwiller-Helfenfinger, E., & Perren, S. (2016). The

relationship between adolescents’ bully-victim problems and their

use of mechanisms of moral disengagement in the context of passive

moral temptations. Paper presented in the symposium Moral

disengagement in the production of progression (Chairs: K.

Runions & E. Gutzwiller-Helfenfinger). 22nd World Meeting of

the International Society for Research on Aggression (ISRA),

Sydney (Australia), July 19-23, 2016.

Gutzwiller-Helfenfinger, E., & Perren, S. (2015). Adolescents’

evaluations of passive moral temptations – relations to

bully-victim problems. Paper presented in the symposium

Morality and Bully-Victim Problems (Chairs: L. Kollérova

& D. Strohmeier). 17th European Conference on Developmental

Psychology (ECDP), Braga (Portugal), September 8-12, 2015.

Heinrichs, K. & Wuttke, E. (2016). Mangelnde Financial

Literacy der Kunden als moralische Herausforderung beim Verkauf

von Finanzprodukten? – eine kontextspezifische Analyse im Licht

der Happy-Victimizer-Forschung [Lack of consumers’ financial

literacy as a challenge for sales in financial insustry – a

context specific analysis in light of Happy Victimizer research].

In G. Minnameier (Hrsg.). Ethik und Beruf – Interdisziplinäre

Zugänge (S. 199-214). Bielefeld: Bertelsmann.

Heinrichs, K., Kärner, T. & Reinke, H. (2020). An

action-theoretical approach to the ‘Happy Victimizer’ Pattern –

Exploring the role of moral disengagement strategies on the way to

action , Frontline Learning Research, 8(5), 24-46.

doi: https://doi.org/10.14786/flr.v8i5.386

Heinrichs, K., Minnameier, G., Gutzwiller-Helfenfinger, E. &

Latzko, B. (2015). „Don’t worry, be happy“? – Das

Happy-Victimizer-Phänomen im berufs- und wirtschaftspädagogischen

Kontext [The Happy Victimizer Phenomenon in a vocational and

business educational context]. Zeitschrift für Berufs- und

Wirtschaftspädagogik, 111(1), 31-55.

Forsythe, R., Horowitz, J., Savin, N., & Sefton, M. (1994).

Fairness in simple bargaining experiments. Games and Economic

Behavior, 6(3), 347-369.

Keller, M., Lourenço, O., Malti, T., & Saalbach, H. (2003).

The multifaceted phenomenon of ‘Happy Victimizers’: A

cross-cultural comparison of moral emotions. British Journal

of Developmental Psychology, 21 , 1–18. doi:

10.1348/026151003321164582

Klein Schiphorst, A. T. (2013). Students’ justifications for

academic cheating and empirical explanations of such behavior. Social

Cosmos, 4(1), 57-63.

Krettenauer, T. (2011). The dual moral self: moral centrality and

internal moral motivation. The Journal of Genetic Psychology,

172(4), 309-328.

https://doi.org/10.1080/00221325.2010.538451

Krettenauer, T., Asendorpf, J. B., & Nunner-Winkler, G.

(2013). Moral emotion attributions and personality traits as

long-term predictors of antisocial conduct in early adulthood

Findings from a 20-year longitudinal study. International

Journal of Behavioral Development, 37(3), 192-201. doi:

10.1177/0165025412472409

Krettenauer, T., Malti, T., & Sokol, B. (2008). The

development of moral emotions and the Happy Victimizer Phenomenon:

a critical review of theory and applications. European

Journal of Developmental Science, 2, 221-235. doi:

10.3233/DEV-2008-2303

Lakatos, I. (1978). The methodology of scientific research

programmes: Volume 1: Philosophical papers . Cambridge

University Press.

Latzko, B., & Gutzwiller-Helfenfinger, E. (2014). Happy

Victimizer im Erwachsenenalter: Rekonstruktion eines Phänomens?

[The Happy Victimizer in adulthood: reconstruction of a

phenomenon?] Vortrag an der 23. Tagung des Arbeitskreises Moral

(Deutschsprachige Moralforscherinnen und Moralforscher), Hannover,

9.-11. Januar 2014.

List, J. A. (2007). On the interpretation of giving in dictator

games. Journal of Political Economy, 115(3), 482-493.

doi: https://doi.org/10.1086/519249

Malti, T., & Buchmann, M. (2010). Socialization and individual

antecedents of adolescents‘ and young adults‘ moral motivation. Journal

of Youth and Adolescence, 39, 138-149. doi:

10.1007/s10964-009-9400-

Malti, T., Gasser, L., & Buchmann, M. (2009). Aggressive and

prosocial children’s emotion attributions and moral reasoning. Aggressive

Behavior, 35(1), 90–102. doi: 10.1002/ab.20289

Menesini, E., Sanchez, V., Fonzi, A., Ortega, R., Costabile, A.,

& Lo Feudo, G. (2003). Moral emotions and bullying: A

cross-national comparison of differences between bullies, victims

and outsiders. Aggressive Behavior, 29(6), 515–530.

https://doi.org/10.1002/ab.10060

Minnameier, G. (2020). Explaining Happy

Victimizing in adulthood – A cognitive and economic approach,

Frontline Learning Research, 8(5), 70-91.

https://doi.org/10.14786/flr.v8i5.381

Minnameier, G. (2018). Reconciling morality and rationality:

Positive learning in the moral domain. In O.

Zlatkin-Troitschanskaia, G. Wittum & A. Dengel (Eds.).

Positive learning in the age of information (PLATO) - A blessing

or a curse? (pp. 347-361). Wiesbaden: Springer. doi:

10.1007/978-3-658-19567-0

Minnameier, G., Heinrichs, K., Kirschbaum, F. (2016).

Sozialkompetenz als Moralkompetenz – Wirklichkeit und Anspruch?

[Social competence as moral competence – reality or expectation?]

Zeitschrift für Berufs- und Wirtschaftspädagogik, 112(4),

636-666.

Nunner-Winkler, G. (2013). Moral motivation and the Happy

Victimizer Phenomenon. In K. Heinrichs, F. Oser & T. Lovat

(Eds.), Handbook of moral motivation. Theories, models,

applications (pp. 267-288). Rotterdam: Sense Publishers.

Nunner-Winkler, G. (2008). Die Entwicklung des moralischen und

rechtlichen Bewusstseins von Kindern und Jugendlichen [The

development of moral and legal awareness in childhood and

adolescence]. Forensische Psychiatrie, Psychologie,

Kriminologie, 2, 146-154.

https://doi.org/10.1007/s11757-008-0080-x

Nunner-Winkler, G. (2007). Development of moral motivation from

childhood to early adulthood. Journal of Moral Education, 36(4),

399-414. https://doi.org/10.1080/03057240701687970

Nunner-Winkler, G. (1993). Die Entwicklung moralischer Motivation

[The development of moral motivation]. In W. Edelstein, G.

Nunner-Winkler & G. Noam (Hrsg.), Moral und Person

(S. 278-303). Frankfurt a.M.: Suhrkamp.

Nunner-Winkler, G. & Sodian, B. (1988). Children’s

understanding of moral emotions. Child Development, 59,

1323-1338. doi: 10.2307/1130495

Nunner-Winkler, G., Meyer-Nikele, M., & Wohlrab, D. (2006).

Integration durch Moral: Moralische Motivation und Ziviltugenden

Jugendlicher [Integration through morality: moral

motivation and civic virtues in adolescence]. Wiesbaden:

VS-Verlag.

Oser, F., & Reichenbach, R. (2005). Moral resilience: What

makes a moral person so unhappy. In W. Edelstein & G.

Nunner-Winkler (2005). Morality in context (pp.

203-224). North Holland Publishing: Elsevier.

Parche-Kawik, K. (2003). Den homo oeconomicus bändigen. Zum

Streit um den Moralisierungsbedarf marktwirtschaftlichen

Handelns. [To handle the homo oeconomicus.

Contribution to the discussion about the need for morality in

economic markets] Frankfurt/M.: Peter Lang-Verlag.

Perren, S., & Gutzwiller-Helfenfinger, E. (2012).

Cyberbullying and traditional bullying in adolescence:

Differential roles of moral disengagement, moral emotions, and

moral values. European Journal of Developmental Psychology, 9(2),

195-209. doi: 10.1080/17405629.2011.643168

Pies, I. (2009). Moral als Heuristik: Ordonomische Schriften zur

Wirtschaftsethik [Morality as heuristics: Ordnonomic papers on

business ethics]. Berlin: wvb.

Smetana, J. G. (2006). Social domain theory: Consistencies and

variations in children’s moral and social judgments. In M. Killen

& J. Smetana (Eds.), Handbook of moral development

(pp. 119–154). Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum.

Sticca, F., Ruggieri, S., Alsaker, F., & Perren, S. (2013).

Longitudinal risk factors for cyberbullying in adolescence. Journal

of Community & Applied Social Psychology, 23(1), 52-67.

https://doi.org/10.1002/casp.2136

Vallerand, R. J. (2000). Deci and Ryan's Self-determination

Theory: A view from the hierarchical model of intrinsic and

extrinsic motivation. Psychological Inquiry, 11(4),

312-318.

Wainryb, C., Brehl, B. A., & Matwin, S. (2005). Being hurt and

hurting others: Children's narrative accounts and moral judgments

of their own interpersonal conflicts. Monographs of the

Society for Research in Child Development, 70, 1–114.

https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-5834.2005.00354.x

Weiner, B. (2013). Ultimate and proximal (attribution-related)

motivational determinants of moral mehaviour. In K. Heinrichs, F.

Oser & T. Lovat (Eds.), Handbook of moral motivation.

Theories, models, applications (pp. 99-112). Rotterdam:

Sense Publishers.